AS EARTH’S GRAVITY SLOWLY WEAKENED, NO PART OF THE CIRCUS WAS MORE GREATLY IMPACTED THAN THE TRAPEZE ACT.

Some circuses incorporated weights that approximated traditional gravity, but in addition to throwing the artists off balance and being cumbersome, customers were increasingly less impressed.

“At this point, what are they defying?” they asked, eyeing the largely vestigial nets skeptically.

In fact, trapeze had gotten considerably more dangerous even as popularity waned.

While the risk of falls was gone, without an enclosed tent you could float dangerously upward. Worse was the new debris in the air that created an opportunity for kids mature enough to understand capacity to harm, but not so mature for the morality of their actions to register. First came cotton candy, then sand, glue-dipped feathers, and shattered glass bits. The Internet apparently contained all sorts of cruel suggestions.

Some circuses moved to spaces artificially set to Earth’s old standard gravity. Unfortunately for them, artificial gravity spaces of all kinds quickly went out of fashion as the younger generation found it unpleasant and had no nostalgic desire to experience what was once normal. Troupes that invested heavily in this tactic folded within a generation, including Circus Rainer and the venerable Circus Poe.

Circus Thumbelina avoided the standard gravity boom and crash entirely. In fact, Circus Thumbelina had weathered many fickle audience trends for decades. They’d used freak shows in the early years but fired them long before bad press forced industry changes. Circus Thumbelina never had elephant or wild-cat acts, preferring dogs, pigs and occasionally bee beards, and so didn’t lose much business when non-domesticated animals went out of fashion. Much of their luck was more a matter of low overhead than ideology. More recently, they struggled with industry antiquation coupled with declining birth rates.

With fewer children in the audience, management expanded the trapeze act. Aerial acts were popular with adults, many of whom recreationally attended trapeze schools as therapy.

As trapeze took up a larger portion of circus performances, Harold Flynn rose through Circus Thumbelina’s rank. First, he managed its aerial acts and later the entire eighty-person operation. All the while, he continued choreographing his own routines. He had as good a life as anyone in the industry.

At age 30, shortly before he joined management, a woman known as Iris Summer noticed him. Four years younger than him, Iris’s skill was plate spinning, devil-sticks, and other object manipulations. On her waist was the faint outline of a pussy-willow tattoo that she’d tried to remove. He didn’t ask her real name, but not knowing bothered him.

Thinking himself subtle, he gave her an expensive deck of cards decorated with Georgia O’Keeffe flowers wrapped in butcher-block paper. He gave them to her during crew lunch, when most people sat lazily near the equipment of their act; mingling was common but noticed. She discreetly placed the cards out of sight with slight of hand, a smile and soft nod, then looked around with caution.

He thought his gesture was a failure, and uncharacteristically missed several easy catches during practice that afternoon. He debated internally whether he’d either been softly rejected or if he’d been too subtle.

That evening, after the show, she slipped a note under the flap to his tent. Her handwriting looked like floating ribbons.

Oh my goodness, Harold.

Thank you for the pussy playing cards. They are lovely.

-Iris

Women, who have always understood the language of subtlety better than men, also understood when it was unnecessary.

He kept thinking of her vagina, hidden from him beneath towels or skimpy circus outfits that looked like gaudy bathing suits. He wanted to say to her, “O’Keeffe could never paint a flower more beautiful than yours; the task is beyond human skill.” The line would have made no sense, given that he’d never seen her naked and so was only working off what he could see: her hazel eyes, her thin hands, her grace with objects.

By the time he discovered that he was correct, he’d forgotten his clever words.

*

A dozen years later, now 42, Harold stepped into his and Iris’s private tent. For the first time, gravity grew weak enough that the deck of flower cards scattered and floated, lifting off on their own without being tossed. Several lightweight, decorative plates spun endlessly, held in the air only by a little twine. Either she was practicing a new act or she simply liked how they looked.

Iris was topless, serious, familiar, occasionally batting away a stray card that came too close while she put on her makeup. She’d pre-emptively taped down her makeup brush, compact, and other little things so they couldn’t escape. Twin photos of young her and her childhood dog Buddy remained anchored to the vanity by its metal clamshell, but its necklace chain floated like a reverse kite.

With no greeting, Harold launched right into how Circus Gaudilliere had incorporated playful tricks into their trapeze. Slight of hand and banter. He was firmly against it. That would make trapeze artists, at root, additional clowns.

He didn’t look down on buffoonery like some trapeze artists did, but comedy was a distinct skill. All circuses needed the acts and the clowns, he explained. “We complement each other. We pretend one is for the kids, the other to entertain the adults, but both, in fact, break up exhaustion and keep attention. A circus with only clowns wouldn’t last.” Anyhow, he didn’t have time to retrain. Slapstick was not his job, nor what he was good at. He was the show’s gravitas, not the jokester.

As he voiced his concerns, his sour mood receded. He wanted Iris like when they were courting, and searched for the cause. The floating pussy flowers triggered memories, vague at first, then coalesced around his unused pickup line.

“You know what they used to call devil-sticks?” she asked after he finished.

“What?” he said absently, looking at the cards like his head was in clouds.

“Gravity sticks. What’s the point of them now?” His self-absorption irritated her. “We’re both going through this.”

But his lousy mood was gone — as though he’d passed it on to her — and he wouldn’t be sucked back in. He proudly said his line about O’Keefe being unable to paint her pussy, and shared the history.

She rolled her eyes then faced fully forward toward her mirror. “Well, I’m glad you didn’t use that then,” she said. His reflection looked hurt. She sighed and added, “What you said didn’t matter. I knew who you were. Come.”

“Perhaps my line was true in two different ways: the pussy I imagined you would have was more lovely that anything she could paint, and the one you have, that I finally saw, was more beautiful than that.”

“We have a show,” she said. Even seated as she was, her legs came together protectively. “We don’t have time.” They both knew this wasn’t true. The show hadn’t started as scheduled in years.

“We’ve got time,” he said.

He spouted sweet nonsense: How her vagina had a personality informed by, but distinct from Iris’s. Like Iris, her pussy was quiet but not shy. Unlike Iris, it communicated its arousal, wants and needs without fuss or guile, using wetness, hip gyration and contractions in place of words. Iris, and all other vaginas he’d met, acted downright aloof by comparison. “For example,” he said, “just now, your pussy would like to be on top of me to control our tempo.”

Oh goodness what nonsense! Her hips weren’t even part of her vagina. Thankfully he hadn’t said that stupid line back then, before they’d dated; the cards had been a clumsy enough gesture, at lunch! Clowns right nearby! Shouting his intentions to the world. She’d stared at the cards all afternoon not knowing what to do, debating. She’d known long before him that they were a good match, and had been signaling for his attention, making excuses to be near him. She’d been on the fence only because of his obvious arrogance.

She’d had bad luck with arrogant men before. His shyness sometimes came out as arrogance. But then he could also actually be arrogant. More often back then, with his constant promotions within the circus while trapeze boomed relative to other acts, which made his head swirl a bit. Only when the trapeze was hit like the rest of circus’s decline did she feel any certainty that he was a good man.

Now, he teased her.

Now, he was saying that the only verbal words her vagina had ever spoken were in her note slipped under his tent flap. His boldness in giving the gift had made her bold, it was true.

What of Harold? She imagined his cock’s personality as that of a perennial teenager: energetic, chivalrous — never coming first — and always earnestly overeager for its nightly visit. The rest of Harold’s body was easy on the eyes. Even after those near misses in trapeze where hands don’t quite connect, he fell gracefully and gave the crowd a smile that said “all part of the show.” She liked tending to his scrapes and rope burns afterward, which had been replaced with cuts from shrapnel or whatever the dumb kids tossed in the air. Back then his cuts healed faster. Back then he had more muscle too, and flew through the air in fluid movement and instinct.

Back then everyone had more muscle.

Goodness. Now he was going on about wanting to worship her pussy, and leave an offering. His body this. Her body that. She stopped listening. From the beginning, he was more comfortable expressing love towards the parts of her body than to her self. He’d declared love to three distinct body parts before her. She allowed this — if this helped him express his feelings, what harm was there? She translated and received the same message. She scratched his neck and whispered “I love you.” He quieted, still had trouble saying it back directly. Instead, he carried her to their bed, positioning their fall so that she would be on top.

While beneath her, his saliva collected in his mouth, between gums and cheeks. He let it. This slow collection wasn’t abnormal unto itself, and could be helpful if her vagina asked to feel his tongue.

Then something happened that had never happened before. The saliva built too much, pooled into a small river and traveled to the base of his throat, slowly evoking a drowning sensation. After an unsuccessful swallow down the wrong path, he tried to focus on his lover, on the floating cards, on her animal gyration, on trying to help guide Iris’ pussy to the shake of an orgasm.

None of this worked. He focused on her breasts’ bounce, how now they only returned to set position slowly. Despite the moment’s erotic charge, it was only a matter of time before he’d startle Iris with a frightening coughing fit. He needed to act. Regretfully, he patted Iris’s waist. She dismounted. His apology came out as a hacking wet cough.

Harold excused himself and retreated to the restroom several tents over, infused with shame. Suddenly alone, he still sensed Iris surrounded by the floating cards on the bed. He tried to blame the coughing fit on the change in gravity, but couldn’t find a link.

In the bedroom Iris looked blankly at a nearby advert in the style of Sallie Gardner at a Gallop: the twelve sequential silhouettes trapezing instead of galloping. They could still make the 9pm informal actual deadline for the show’s start if he returned soon. Something had gotten into him. Perhaps the fact that Earth gravity had weakened enough that cards were now floating had forced an acceptance that this stage of their life was done. And then the coughing, perhaps he was hit with how vulnerable they were without insurance. If that was the root issue, she’d tell him about her secret emergency fund. She’d hid money only out of concern he’d want to spend it to save the circus, and it wasn’t nearly enough for that (no amount was). If he needed emotional intimacy, she’d finally tell him she was born Rosemary Loom. He’d like that her given name also sounded like a stage name. He’d tease her and forget his mood. He’d like that she waited a decade of marriage to share, and had chosen now.

In the bathroom, Harold’s only thought was that the coughing fit marked a milestone. Iris had witnessed evidence of his mortality, and he felt shame in this weakness. Her body had not yet failed a basic task, and object manipulation had not yet been ruined to audiences like trapeze, but now that g-force was weak enough that cards were floating, her skills would inevitably become outdated like his as the phenomenon worsened. Everyone’s would. Until finally a new generation would be born that wouldn’t think to go to the circus at all.

*

The next day Harold would call his father, leaving out the more sordid details, and his father would click his tongue and say, “Dysphagia, that’s all. Just normal wear and tear.” The mouth and throat muscles loosened as a natural part of aging, his father explained. Harold should get used to this. Harold would learn techniques to avoid the risk of misswallowing as time passed — eating slowly and tilting his head back as he drank — but for now, his father said, “this is just a new fun concern that will be with you until death.”

*

But that conversation was in the future.

In the moment, Harold returned from the bathroom to their bed after drinking water and relieving himself. Iris’s eyes were full of questions but Harold just shook his head and said, “I’m fine. It was nothing.”

Perversely, the couple’s urgency and passion increased. Their bodies’ more severe future failings loomed, but they were still comfortable and sound for the moment. In Harold’s mind, they made a silent pact to enjoy their health while health lasted. Their resumed physical intimacy was their most enjoyable in months, despite — or because of — the small reminder that everything they knew would someday disappear.

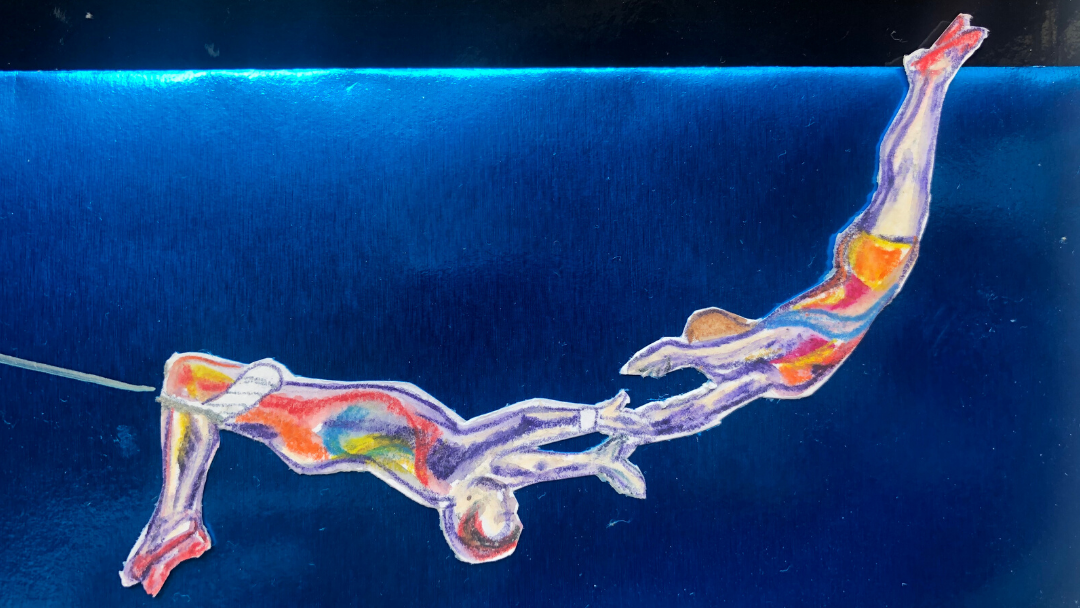

This might be their last chance to feel pleasure in this world (or, at least, in this version of this world). He grasped the challenge with both hands and made love with such vigor that, as they lifted off the bed, they continued in the air without noticing, twisted sheets joining them and spreading like wings, their bodies floating.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories or poetry sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

OR grab a print issue

Stories, poems and essays in a beautifully designed magazine you can hold in your hands.

GO TO ISSUESNEW book release

I’ll Tell You a Love Story by Couri Johnson. Order the book of which Tim Jeffries said, “Surprising in their originality, filled with broken wisdom, and with a refreshing use of language and imagery, these are stories to savour and mull over one at a time but which add up to a satisfying whole.”

GET THE BOOK