EVEN BEFORE HE WAS BORN, HIS HOUSE HAD TAKEN ON THE SIZE AND SHAPE OF WAR. This in itself was not surprising; war can be a liquid or a gas; it will continually seek the levels of rooms. It will embrace corners. It can envelop any space. It can snare itself in the fabric of a shirt, attach itself to a heartbeat, a shared proximity, a desperation.

These two people at war, and along comes a little one.

***

The boy was born, and the boy grew. War continually pressed itself against the pads of fingers, the backs of the eyeballs. By the time he could walk, bowlegged and diapered, war was relentless, was unsparing collisions in the forced channels of this trio, these three. War an aria in the blanched, locked-arm tumble of what passed for their love.

War rang out at night down the hallways, lay clouded in the white shards of shattered kitchen-floor crockery, in the plaster-and-lathe holes in the wall that the boy cautiously laid his little-boy fists into as if in experimentation of the man he may or may not become.

And his good clean desk at school where he rested his head, where he pressed his eyes against the crook of his arm until stars hummed purple against the darkness there. The teacher’s voice like an incantation.

***

The boy cultivated silence, watchfulness, lived around the corners of events. Trod the living room as if it was laden with landmines. Their bodies lay stilled on the bed, lungs hung light with shallow breaths.

War clung like clotted salt to their lips.

War clacking sharp against the rims of bottles, the veiled code of scabs in the crooks of their arms.

War, stubbornly veined inside their bodies like minerals threaded through stone, and to the boy, the world was simply the world. The home a gathering of walls and unknowing.

***

It was just the boy and his father one day and they pulled into a parking lot and the father saw a man coming out of the store. The man was smacking a pack of cigarettes on the back of his hand and the father got out and walked over to the man, whose eyes widened in recognition. The father hit the man once and once again, and when the man crumpled to the pavement the father brought his paint-spattered workboot up into the man’s mouth and a small red tornado spilled out and that was an example of how war filled the spaces of things, how the boy understood it was a thing you carried with you all the time. Birds wheeled darkly in the sky and the boy kept his eyes pinned on an advertisement for milk as the father got back into the car and began speaking feverishly to the boy.

You need to understand, people will take and take from you, his father said.

War was like a shirt he wore, a bone he brushed his hair with.

***

The boy grew. He lay with his face towards the wall, he hung his eyes in books, worlds, heroes. His father struck his mother and left the house, a door slamming so hard that the window cracked like a broken tooth. War trailed his father like a balloon lashed to his wrist by a string. His mother wrapped her hand in a white towel dotted with small blue birds and carefully heated a butter knife on a stove burner until the tip glowed a dull orange. She walked to the kitchen table, which had belonged to his father’s mother when he himself had been a child, and the mother carved unspeakable things into the wood as tears slipped like small pearls from her lashes.

And that was war, and this was, and this was, too.

***

They got a flat tire and a family pulled over to help them and his father leaned forward to get the spare tire from the trunk and two syringes fell from his shirt pocket onto the ground. My wife is diabetic, his father said.

***

He stayed small and curled, like a plant feeding itself from a single wedge of sunlight.

His father wore a sleeveless black shirt that said FUCK SHIT PISS BITCH DAMN in white letters.

His father got fired from his job and drank the next day and then went over to his boss’s house with a small back gun and the boss’s son opened the door, afraid. The father said some things to the boss’s son and walked away and then the police came to their house and took the father, bleary and tired by then, away in handcuffs. And for a bit of time the war retreated. There was some lesson to be learned there, but the boy wasn’t sure what it was.

***

He grew older, soon understanding that war could ignite in the way someone entered a room. The way a tongue fell across teeth and culled words from the air. War could be announced in the unnameable architecture of a hand forming a fist.

***

This is not to say that he was not loved. Love and wartime breathed together in the same room. Joy flickered sometimes, quick as the flash of a knife. War rose to the ceiling while love walked on the floor, low-slung like an animal. Love tough as sinew, love culled from the smallest pieces offered. A love in spite of.

***

The father died eventually. Long after he had left them. He died in a ramshackle trailer beside a river studded with moss-furred stones. It was a beautiful place, but the inside of the trailer was squalid and, of course, war-shaped. The place was suffused with it.

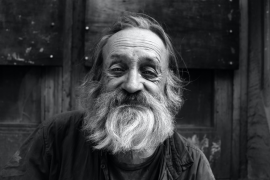

He died, the father, full of lamentations and sorrow and guilt, and later someone found him in the trailer – someone whose love was a duty, someone who remembered the father from when war had not yet conformed to his shape, had not devoured him. They found a small shrunken thing in the bed, all the life in him skimmed off like the skin from a cream, and the boy would have recognized that as war, too.

***

He was told about his father’s death over the telephone, years after they had last spoken. I suppose, the person said, that I have a legal obligation to tell you this, if not a moral one. The person was angry at the father, at the boy, at time’s ceaselessness, at the way war took and took and took.

***

And okay, a story demands an arc. Closure. A beginning and an end.

But there’s none here.

War dismantles narrative.

War gibbers and strides down the backbone of the world, shouting nonsense.

The mother grew old; her world shrank to fit small things in small rooms where war was not allowed, but it didn’t work. Her heart took small steps. The boy, even as he aged, still walked as quietly as he could along the skin of the world. War hung cloudlike, patient, watchful.

***

The boy was only an infant when the mother looked down at her arm and said, I can’t feel anything. We got ripped off, baby.

The father, eyes half-lidded, fell back with his hands curled in his lap. I don’t know, he said slowly. That’s weird. The hypodermic resting on his thigh like a dislodged bone, like an admonition. Years later he would admit to shooting the mother up with water, taking both doses for himself.

Both achingly young, the two of them, nearly children themselves and snared already, wood paneling on the walls, yellow shag carpet, a television tinting everyone an irradiated green, and this new little baby writhing on the couch, arms snared tight in a blanket.

War blooming just like flowers all over the floor, here and here and here.

KEITH ROSSON is the author of the novels Smoke City, an IPPY Silver Medalist for Fantasy and a Silver IBPA Benjamin Franklin Award Winner, and The Mercy of the Tide, which was on the preliminary ballot for the Bram Stoker Award and optioned for film by an executive producer of Game of Thrones. His novel Road Seven will be released in 2020. His short fiction has appeared in Cream City Review, PANK, December, Outlook Springs, Redivider, and more, and has been short- or longlisted for the Birdwhistle Prize for Short Fiction and the New American Fiction Prize. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories or poetry sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

OR grab a print issue

Stories, poems and essays in a beautifully designed magazine you can hold in your hands.

GO TO ISSUESNEW book release

We’re thrilled to release our first novel into the world. Alligator Zoo-Park Magic by C.H. Hooks has been called “A new spin on the mystical, mythical south.”

GET THE BOOK