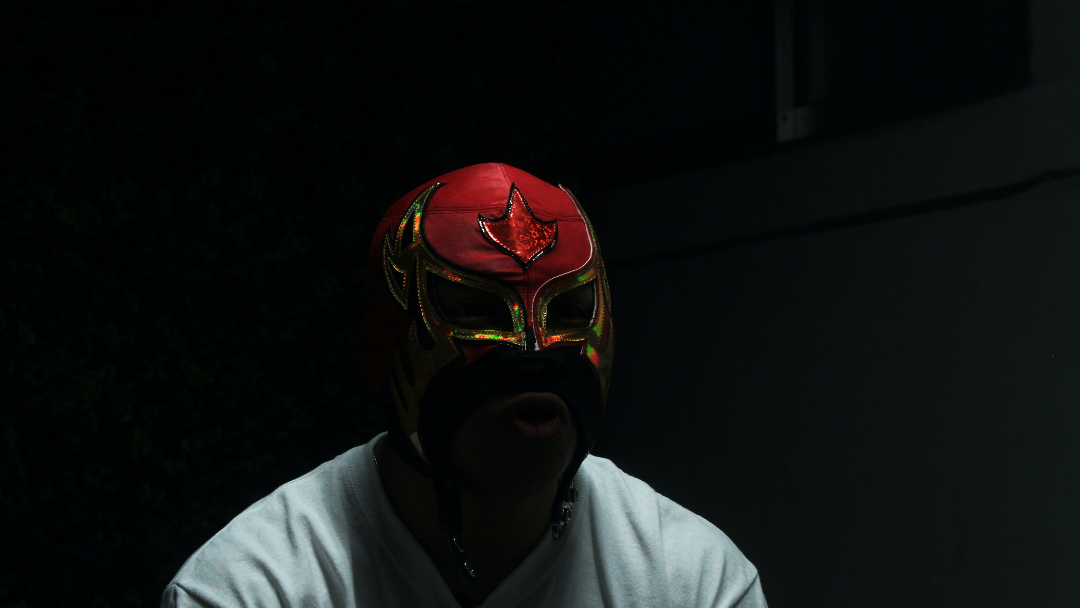

OMAR EXPLAINS TO ME THAT MEXICAN WRESTLERS NEVER REMOVE THEIR MASKS IN PUBLIC.

“Who they are in the ring is the same person they are outside,” he says.

“So The Blue Demon doesn’t remove his mask to eat chicken fried steak?” I ask.

“If it don’t fit into the mouth hole of the mask, he don’t eat it,” Omar says. “Picky eaters, those luchadores.”

His nurse comes in, and we get quiet. Like we’re talking about her. But really, it’s because two grown-ass men talking about wrestling is embarrassing. Two weeks ago, Omar was in the ICU after he died, technically, for three minutes. Today, he’s in a private room and awake and back on his bullshit. The nurse leaves.

He leans over. I lean in, too.

“Man, she had to wipe my ass,” he says. “She asked if I needed help getting to the bathroom, and I told her I was good, but then I had to sit, and I got stuck. I was there so long, my legs fell asleep.” He lays back.

“She seems nice,” is all I can manage to say before I start to giggle.

“Thirty-nine years old, and I have some twenty-year old wiping my ass,” he says. “How did I get here?”

Omar has always been built like a Vaudeville giant. In the seventh grade, he looked like a grown man. By the tenth grade, he was as massive as a drive-in screen with eyeballs. For twenty years, it wrecked his knees and his kidneys.

“There’s a barber shop off Surf street,” Omar says, “The head barber used to be a luchador. He learned to cut his hair because he couldn’t find a trust-worthy barber to go maskless with. Found out he made more money cutting hair than lucha libre.”

“We should go there when you get out,” I say.

“He won’t say nothing,” Omar states. “It’s kayfabe. The wrestlers want to keep up the show no matter what.”

“I’m just talking haircuts,” I say. “I don’t want to fight the guy. Kayfabe or whatever.”

“Ha!” he laughs and immediately holds his ribs.

He starts storytelling about a 70’s wrestling valet named Bertha Mills. That Bertha would gather the capes, jackets, and wardrobe for the wrestlers once they got into the ring. That she’d bring them to the locker room, and every time she’d enter, the wrestlers would yell out ‘kayfabe’ as a warning to stay in character around her.

“Bertha thought it was because she was a woman. She’d go back, and they’d stop cussing or put away their cigars or stop spitting their chaw,” Omar explains. “And after five fights and five trips to the back, Bertha says, ‘Fellas, I don’t mind the cursing or carrying on, but my name is Bertha Mills, not Kay Fabe!’” He makes himself laugh again. He makes me laugh. He holds his ribs.

“You think you missed the boat?” I ask. “The wrestling, I mean.”

“Nah. I wasn’t ever a good actor,” Omar says. “I should have been a comedian, though. Can’t do stand-up from a wheelchair.” He holds his ribs again. “The laughing doesn’t hurt. Just my body.”

“Yeah, well, it’s killing me,” I say.

Two weeks ago, I thought I was saying my goodbyes to him. His brother called. His heart stopped and things weren’t looking good. He had been intubated.

When I arrived, he was awake, but not talking. He was writing on a small whiteboard. I kept waiting for him to write out the joke.

Hey, so I died. Do not recommend.

This is what it takes for you to visit me?

Bro, let’s set off the fire alarm.

Instead, he wrote Why is this happening? Am I not a good pers… The writing trailed off. His hands were already as big as bear claws, but the medications pumping into him caused them to swell into water balloons. He could barely hold the marker.

“When I get out, I’m making changes,” he assures me. “Gonna clean up the diet. Gonna get into shape. Gonna get right with God.”

“Should I write this down?” I ask.

“Yes!” he says. “Hold me to it. I’m gonna see my daughter graduate. Gonna walk her down the aisle. Gonna see my boy go to college. Gonna go to the Grand Canyon.”

“Slow down,” I say. “Let’s start small. Eat. Walk. Run.”

“Shit! Write that down,” he says. “And underline it. Gonna shit on my own. Oh, and this.” He makes the universal sign for sex, followed by masturbation, and a third one I can’t place.

“I didn’t catch the last one,” I say.

“That’s the sign for stealing home,” he says.

His whole body moves as he laughs. He quakes. It’s loosens some of the wiring monitoring his massive body’s vitals. The nurse comes back in frowning.

“Kay Fabe!” he calls and coughs as the nurse enters. I hold my head.

“Mr. Navarro,” she says. “I told you my name is Carla. It looks like you and your friend carrying on made one of the leads fall off. Ya’ll gonna have to keep it down. And anyway, you have rehab in 30 minutes. You need some rest, okay?”

“I died,” he tells her as she reaffirms the leads. “I think I’ve had all the rest.”

“Hush,” she tells him. “You go on now.” She gives me a shooing hand as she leaves.

“She’s right,” I say. “I’m gonna head out, but I’ll be back to visit on Friday. Holler at me if you get bored or vertical before then.”

“Okay, bro,” he says and grins. He looks so much better. I think. I hope.

“Hey, my list?” he asks.

“You really wanted me to write that down,” I say. “I am sorry, bro. I am completely useless.”

“You absolutely are,” he says. “But, hey, at least you can wipe your own ass.”

We laugh uncontrollably. He rips open his stiches, and we have to call the nurse to reclose his wound.

Hailing from Denton County, Texas, ABRAM VALDEZ is a lapsed poet, working by day as an instructional designer and full-time dad. His work has been featured in Eunoia Review, Fourteen Hills, Margie: The American Journal of Poetry, Milk Magazine, and DASH Literary Journal. He’s currently plying his trade in fiction 1,000 words at a time. “1,000 Words on Kayfabe” represents his first flash fiction publication.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories or poetry sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

OR grab a print issue

Stories, poems and essays in a beautifully designed magazine you can hold in your hands.

GO TO ISSUESNEW book release

China Blue by Catherine Gammon. Order the book of which William Lychack Jeffries calls “a fiery declaration of all that is inexpressible about desire and loss and the need to find a home in a world in which even the most solid and real of things feel often less than completely solid or real.”

GET THE BOOK