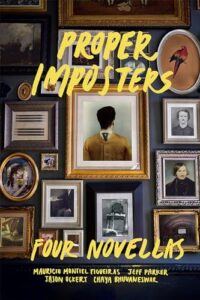

Novellas. 206 pgs. Panhandler Books. January 2024. 9780991640485.

As its title suggests, Proper Imposters is a collection of stories about muddied identities. Within each of its four novellas—written by four different writers—are characters who don’t know themselves as well as they think; or they are aware and active in their pursuit to know themselves better. Each can be read in one sitting but should be given their due before moving on to the next. Even in small bites, there’s a lot here to chew, and even more to digest.

As its title suggests, Proper Imposters is a collection of stories about muddied identities. Within each of its four novellas—written by four different writers—are characters who don’t know themselves as well as they think; or they are aware and active in their pursuit to know themselves better. Each can be read in one sitting but should be given their due before moving on to the next. Even in small bites, there’s a lot here to chew, and even more to digest.

Crowd by Mauricio Montiel Figueiras

Kafka works for a pencil factory. No, I’m sorry. Abel works for a pencil factory. He is a pencil pusher, the kind of man some loathe to be, so much so, he must escape himself. In Crowd, political violence—demonstrations—are the weather. They bookend the narrative, coalesce with the falling snow, and leave us teetering in the void, unsure what is real and imagined.

Mauricio Montiel Figueiras writes pathologically poetic. A spine is described as a hat rack, a riot as a symphony. Each sentence vibrates and buzzes, feeding the tension of what may come next. Abel hears a dead person’s voice. He’s assumed a mission. We are privy to little of it, though.

Crowd features a forbidden, mythological elevator; it resides in the pencil factory where Abel works. There is a cockroach scratching about. It has something to say. Crowd operates with this kind of subconscious logic. Some scenes feel certain and alive. Others feel like projections of Abel’s desire, though their existence in the present narrative is left to interpretation.

And in the fog between each, the novella sings.

Abel hears the chant of his name swell to a kind of glory. When he visits a grave, he first finds the missing “i” in “lovng” to be charming, only to later find it disturbing. These off-balance moments feed the surreal, dystopic nature of this world. Abel feels both dead and alive, passionate and apathetic, pathetic and powerful. It depends on the company.

Mauricio Montiel Figueiras’s Crowd sizzles without burdening the reader with its violence. Blood is just another thing that falls and disappears into the snow. It’s only when the snow melts, when we look a little closer, that true devastation is revealed.

G v. P by Jeff Parker

When absurdism is treated seriously, you release magic. There’s Gogol. Poe. A whisper of a K. But mostly it’s Gogol and Poe, united by their fear of being buried alive.

“I’m the greatest writer who ever lived,” G said.

“I’m the greatest writer who ever lived,” P said.

Jeff Parker understands the weight of a word, even a silly one, and will wield it both wildly and with precision. Whether they are in Eastern Europe or Eastern United States, G’s nose is a schnozz, because a schnozz is a ridiculous thing, and these are two very ridiculous, very serious people. Each time schnozz is uttered on the page, the lines teeter just a bit, and we are forced to take our medicine so we can ride the gelatinous dream without inhibition.

G v. P isn’t the bout it suggests it may be. It’s more so a funny contrast of two writers who are often compared to one another. Same age, same fondness for the grotesque—except one is rather silly and another is a bit morose. As their time together grows, their disdain takes root in the soils of jealousy and neurotic delusion. Their reasons for hating each other are just as silly as their reasons for writing in the first place, and it makes for a romp of a story.

As they travel from Ukraine to Western Europe, a gelatinous bubble briefly transports the two to something resembling a ballroom. In a Kansas City restaurant, they impersonate sanitary inspectors in exchange for a questionable, but free, meal. In the present, one is in a ditch while the other has his blood let out.

The ingredients for a good time are aplenty and Parker cooks up something a little raw, but savory all the same—something certainly more satisfying than, say, boiled peanuts.

Lalita by Chaya Bhuvaneswar

What’s more compelling than the ache that comes with unrequited—or perhaps, partially requited—desire? There are few good answers, as Chaya Bhuvaneswar contends in her novella Lalita.

Lalita, our hero, has decided now, as a sophomore in college, she is ready to lose her virginity. Even better, she’s picked her partner: her ex-roommate’s ex-boyfriend.

Now, she just has to set her plan into action.

If you’ve read White Dancing Elephants (you should if you haven’t) then you already know Bhuvaneswar is a master at capturing and illustrating ache. She continues that trend here, and brilliantly transports the reader back to those horny, thorny, lonely, messy, and embarrassing days of undergrad. Yes, even us straight white guys can relate to that.

But there’s something perverse operating under the surface of Lalita’s endeavor—as suggested by its reminiscent title—and as the pages turn, we learn Lalita’s desire is conditioned to certain social dynamics that complicate her sexual pursuits.

It all turns mostly introspective in the second half, in which Bhuvaneswar weaves between heartbreaking and revealing scenes of the past to the repercussions those scenes have on the present. Here, the narrative quiets and reads a bit like The Secret History by Donna Tartt. It’s college, but the stakes feel so much higher, and we’re left unsure what to make of Lalita’s next steps.

There’s something to be said about acknowledging how the past informs the present, while also embracing personal agency when it comes to the present and future. Lalita wants to be free—of cozy-cozy time, of the violence and rage of men, of her fear of winding up alone—but what does it take to achieve that kind of freedom?

The Body Collector by Jason Ockert

Whether it’s a wasp’s sting, a deer carcass, or a discarded tongue, Jason Ockert loves to employ a device that will force a reader to feel the thing. You don’t want to see it, smell it, or taste it, but you do—and like your veggies, you’re better off for it.

The Body Collector is rich with Ockert-isms every reader should adore. There’s the aforementioned discarded tongue; the imagined dialogue with a non-verbal creature; musings of boyhood; some sandbox time with language (deathstyle, anyone?); shadowselves.

Donna is the one who discovers the tongue and the body to which it belongs. Duncan is the one who must change his deathstyle before he dies—again. The latter reads like a Joycean character, one fixated on his own undoing. A version of Ignatius J. Reilly who is capable of self-reflection. The former comes across a little more seasoned, a purer soul, if not equally pathetic.

Ockert wastes no time connecting our heroes through the reintroduction of the tongue. We also learn about something called the Flavor Eraser—a tongue condom and another thing he forces us to feel. This encounter leads us into the second half of our tale and a further exploration of who and what the Body Collector is. Duncan is caught in something supernatural, with seemingly no escape, and Donna can sense it, even if she doesn’t quite know what it is.

In The Body Collector, abrupt change is the nature of the game. Whether that is sudden weight loss, a shift in point-of-view, the transformation into death and life-again, or simply the switch of a light. The turmoil that comes with that kind of whiplash leaves an impression on the psyche. It entices us to forget our physicality, to become lost in the mind, in ideas, which then allows someone or something else to collect that body.

It’s a dark place to play, but Ockert manages to have fun and thanks to his efforts, so do we.

Proper Imposters: Four Novellas is available through Panhandler Books. Purchase it now through their website.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories or poetry sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

NEW book release

Direct Connection by Laura Farmer. Order the book of stories of which Mike Meginnis says there is “an admirable simplicity at their heart: an absolute, unwavering confidence in the necessity of loving other people.”

GET THE BOOK