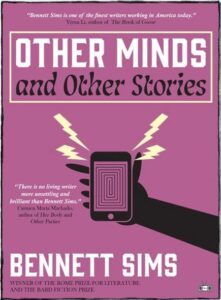

Fiction. 202 pgs. Two Dollar Radio. November 2023. 9781953387356.

Bennett Sims’s experimental collection Other Minds and Other Stories explores the ways we might potentially fail at creating a legacy. When these stories follow a traditional narrative structure—the stalker recording phone calls, a dead lover sending letters in the mail, masked strangers standing in photographs—a chemical heat of anxiety unfurls in my chest. When they lean into a nontraditional, academic narrative, I’m forced into the truth of the thing being told. All of Sims’s work feels uncannily familiar, and I’d argue that this is some of the best horror I’ve read in years.

Bennett Sims’s experimental collection Other Minds and Other Stories explores the ways we might potentially fail at creating a legacy. When these stories follow a traditional narrative structure—the stalker recording phone calls, a dead lover sending letters in the mail, masked strangers standing in photographs—a chemical heat of anxiety unfurls in my chest. When they lean into a nontraditional, academic narrative, I’m forced into the truth of the thing being told. All of Sims’s work feels uncannily familiar, and I’d argue that this is some of the best horror I’ve read in years.

The collection begins appropriately with a brief meditation on our existence after death with “La ‘Mummia Di Grottarossa.'” In this flash piece, Sims describes a room in the basement of the Palazzo Massimo in Rome where “the blackened body of a mummified girl” has been put on display. Children cram into the basement to take her photograph: “Compared with her, the hundred statues on the floors above them bore them [. . .] They can tell that this girl, despite the two millennia condensed in her, is closer to them in time. Like them, she once lived inside it. Now she has passed beyond it” (17).

The horror of legacy comes to mind—the act of being forgotten becomes a cosmic, horrible event. The children remind me of the times at funerals I saw bodies tucked into their caskets, how they seemed more like dolls, and that feeling of the wonder of the body is admitted here in Sims’s work, something I’ve never been able to express. The children blur the boundary of fear and curiosity, which perfectly sets the tone for the rest of the collection.

The first traditional narrative, “Unknown,” manifests real paranoia—the narrator suspects his wife of cheating on him, but he is unable to confront her for fear of breaking the trust of privacy (he saw the messages on her phone); as he tries to get closer to the truth of what’s going on with her, he gets strange phone calls from someone with recordings of his wife’s voice. The nameless protagonist might be sympathetic—we see these things pushing him to behave erratically—while also being a refreshing critique of how technology prevents real communication.

While Sims’s work tends to play with the horror genre, others are far more unusual. In “Pecking Order,” Sims spends thirteen pages torturing a chicken. The protagonist, Kyle, is forced into a situation where he must butcher their egg-laying hens, and he spends the entirety of the story trying and failing to humanely slaughter Judith, the meanest of three chickens he and Audrey have been keeping. Sims makes me care for Judith, despite telling us how terrible she is to the other hens: “He told himself that he had picked her first at random, but the truth was that he was expecting her to be the easiest, emotionally, to murder. She was—alone among their flock, if not among her race—an appalling bully and greedy sociopath” (54). Even though Sims assures us that Judith deserves to be slaughtered, we’re still forced to empathize with these chickens, and the more horrified we feel as the protagonist covers himself in blood.

There are several instances in Other Minds where Sims blurs the lines between fiction and nonfiction, but I find myself thinking little of genre as I read his descriptions of tombs, carvings, photographs, and nightmares; in the longest of his pieces, “Portonaccio Sarcophagus,” he explores memory and legacy beginning with the tomb of Pompilius, an official of Marcus Aurelius. The tomb features an assortment of figures carved into its sides, but the face of Pompilius is left oddly blank. Sims uses these smooth, expressionless face as a focal point for an examination of our legacies: “Death is just the stable framework, the cutout structure, within whose void a million mortal faces blur” (81). Sims attempts to justify the absence of Pompilius’s face: old features might have been sanded off, or the sculptor might have intended to add something there but forgot.

Sims’s examination of blurred identity and legacy reminds him of a photograph of his mother in an Italian cemetery and a strange, faceless being watching over her from behind a grave. Facelessness for Sims is associated with death, and this brings him to the present where he attempts to find his mother on her road using Google Street View, a curious, existential attempt to determine whether the universe has a way of memorializing the people we love. He doesn’t find her, and Street View would have blurred her face anyway, he admits, though Sims offers a glimmer of hope:

I could see the consoling or compensatory side of things. For I had been searching Street View, I realized, not merely for her but as her. The view of the street that I had been afforded was, in a way, her own: whenever I wanted to, I could retrace her steps there, encountering this land of ghosts—blurry, half-familiar—as she might have found it. (93)

If we can’t salvage an image of the person, we learn to see as they saw; maybe this isn’t a solution to grief, but it’s a logical method of keeping those who we’ve lost close to us.

Sims’s work reminds me of Steven Millhauser, often emulating the world of academic writing, though unrestrained, dabbling almost in paranoia. “Portonaccio Sarcophagus” (“unspecified” prose, as the Georgia Review categorizes it) even utilizes photographs of the sarcophagus to lend to its academic-ness. Sims includes an image from Street View, a blank face haunting the black-and-white image. However this is meant to be read, “Portonaccio Sarcophagus” is a convincing, engaging work even given the fact that the entire twenty-seven pages is a single paragraph.

An unexpected joy comes from the way Sims uses genre to express illogical feelings of guilt associated with legacy, and I begin to imagine things as I read to the end of these stories. I’ve never been able to put a finger on what makes horror work for me, but I think this collection has helped me to understand that the most horrifying thing to me is that my fear causes me to devolve and create a logic of absurdity in my head. The chickens must die because if they don’t, Kyle and Audrey will not last. This is a horrifying thought, but believe this. The chickens will live on, in my memory, even if they’re not real—I’m not as concerned with the cruelty as I am with the causal relationship between one thing and another. The characters of Sims’s work have trouble communicating, and I believe that our lack of an understanding of how to communicate with one another is inherently terrifying. But there is also questions of legacy, which I’ve focused on in my review: I will disappear if these children don’t come down into the basement to take my picture. I no longer consider that it doesn’t matter what people think about me after I’m dead—I’m actively concerned with my mortality. Sims makes me consider these illogical thoughts, and that alone makes this collection worth exploring for the literary reader and horror enthusiast alike.

Other Minds and Other Stories is available through Two Dollar Radio. Purchase it now through their website.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories or poetry sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

NEW book release

Direct Connection by Laura Farmer. Order the book of stories of which Mike Meginnis says there is “an admirable simplicity at their heart: an absolute, unwavering confidence in the necessity of loving other people.”

GET THE BOOK