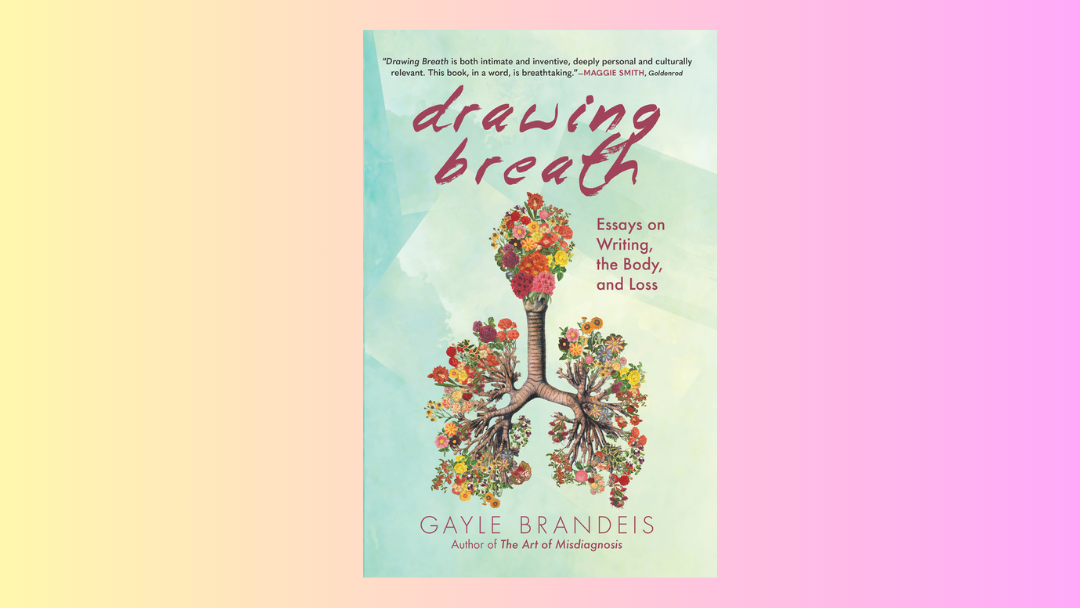

When Gayle Brandeis was three years old, she would hold the Chicago Tribune up above her cereal bowl, just like her parents did every morning. They didn’t realize she knew how to read until one day, she looked up from the paper and said, “Did you know President Nixon has pluh-bitis?” (She hadn’t yet figured out how the “ph” sound worked.) She’s been a voracious reader ever since. She started writing poems when she was 4, another habit that’s continued. Gayle has been writing in multiple genres from a young age—she wrote her first “novel,” The Secret World (inspired by The Secret Garden, one of her favorite books as a kid) at 9, and published a neighborhood newspaper when she was 10—and as she notes in her new essay collection Drawing Breath: Essays on Writing, the Body, and Loss (Overcup Press), she still writes about many of the same subjects she explored as a kid, when she wrote short stories about girls going blind, mothers with eating disorders, teachers having psychotic episodes, and the like, fascinated then and now with what she refers to in her book as “mental and physical illness and the mysteries of the body.”

Gayle is the author of the craft book, Fruitflesh: Seeds of Inspiration for Women Who Write (HarperOne), the memoir, The Art of Misdiagnosis (Beacon Press), and the novels The Book of Dead Birds (HarperCollins), which won the PEN/Bellwether Prize judged by Toni Morrison, Maxine Hong Kingston, and Barbara Kingsolver, Self Storage (Ballantine), Delta Girls (Ballantine), and My Life with the Lincolns (Henry Holt Books for Young Readers), chosen as a state wide read in Wisconsin. Her novel in poems Many Restless Concerns (Black Lawrence Press) was shortlisted for the Shirley Jackson Prize, and two poems from her collection, The Selfless Bliss of the Body (Finishing Line Press) were read on The Writer’s Almanac on NPR. Her poetry, creative nonfiction, and fiction have received several honors, including the Columbia Journal Nonfiction Prize, the QPB/Story Magazine Short Story Award, a Barbara Mandigo Kelley Peace Poetry Award, and Notable Essays in Best American Essays 2016, 2019, and 2020. Gayle currently teaches in the low residency MFA programs at Antioch University, where she received her MFA in Fiction, and University of Nevada, Reno at Lake Tahoe. She’s also teaching a yearlong memoir course through Story Studio Chicago. Gayle, who left the Chicago area in 1986, recently moved to Highland Park, IL with her husband and youngest son.

Megan Vered: I am wowed by how you play with structure in Drawing Breath: Essays on Writing, the Body, and Loss both in the essays themselves and the lay out of the book. Your essays include ingenious techniques like surveys, footnotes, definitions, lists, chants, visual jaunts, and self-interview. What comes first for you? Content or structure?

Gayle Brandeis: Thank you so much! I would say content usually comes first for me, and it announces itself in a variety of ways—a scene, an idea, a question, a sensory impression, a sentence that gets stuck in my head. The content tends to lead me toward the form it needs, sometimes quickly, and sometimes after a lot of trial and error. It became apparent to me pretty early on that “Rib/Cage” was taking on the shape of a rib cage, for example, though I played with that over time, eventually choosing to alternate left and right justification on the page to draw that image out further (and then the wonderful designer Jenny Kimura made this even more clear across the facing pages.)

Vered: What made you decide to write a series of essays rather than a memoir?

Brandeis: It wasn’t a conscious decision—I just wrote essays as they came to me, and continue to write essays this way, without seeing them as parts of a whole, but as wholenesses in themselves, as discrete things I find myself needing to write. I had never envisioned writing a memoir before my mother’s suicide, but even when I found myself being pulled toward that form, I started by writing essays about the experience. I don’t think I had articulated this to myself at the time, but I can see how it felt less intimidating to begin with a shorter form. I just had to go underwater for a little bit and then could come back up for air. After writing a few essays, I felt ready for the sustained deep dive of a book (and I continued to write essays that had a life of their own outside the larger project, as well. I love the essay form so much.)

Vered: What is it about the essay form you love and what, in your eyes, are the fundamentals of an effective essay?

Brandeis: I love how capacious the essay can be.

An essay can veer toward prose poetry/lyricism, focusing on the beauty and rhythm of language, its heartbeat, its breath, can veer toward breathlessness in the use of really long sentences, ones that stretch your lungs, your mind, your idea of what an essay, a sentence can be, even what a word can be—look at fundamental for instance; the words “fun” and “mental” are right inside it, and of course not every essay has to be fun, not every essay has to be mentally challenging, but some are one or the other or both, and each essay dictates its own fundamentals as you write it, tells you what it needs to be whole.

An essay can take on the form of something else, say a recipe:

A cup of family history

A half cup of research

Heaping tablespoons of sensory detail

Enough leavening/levity to help it rise

Mix carefully so you can taste each ingredient, but they’ll also create a cohesive flavor together.

An essay can be

- a braid

- a collage

- full of quotes, like Annie Dillard saying “There is nothing you cannot do with (the essay): no subject matter is forbidden, no structure is proscribed. You get to make up your own structure every time, a structure that arises from the materials and best contains them.”

- a spiral

- a circle

- a patchwork of multimedia

- a list

An essay can be anything you want it to be, centered around a moment, a question, a scene, a theme, an image—whatever is pulsing at the heart of it. The trick is figuring out how to make each word, each sentence, each paragraph reflect that heart, how to make the exploration into that heart feel whole unto itself, even if it’s fragmented or open-ended, how to draw the reader into our private experience, how to make the page breathe with life.

Vered: A page that breathes with life—I’m going to remember that. And thank you for the improvisational dose of hermit crabbing. I’d love to hear more about what inspired you to use the metaphor of breath as the organizing principle for your essay collection.

Brandeis: I wrote the title essay, “Drawing Breath,” as my critical paper when I was getting my MFA over 20 years ago. I’d long been interested in the connection between writing and the body—I’ve been writing and dancing since I was a little girl and created my own BA to explore these two passions, “Poetry and Movement: Arts of Expression, Meditation, and Healing.” I’d realized breath was a potent nexus between these arts—both writing and dance are so impacted by breath (and both impact the breath in turn) and this essay gave me a chance to investigate this connection more deeply. I may have written it to fulfill a program requirement, but it was wildly fulfilling for me to write, and I’m so grateful Antioch University (and my amazing mentor Alma Luz Villanueva) allowed me to dive into such a personally significant project, one that guides me even today. I came to realize this essay provided a kind of template for my nonfiction—looking outward with each exhale, turning inward with each inhale. Writing is like that for me—a constant interchange of self and world, flowing back and forth.

I decided to pull my essays into a collection fairly early in the pandemic, so breath was at the forefront of my mind for other reasons—I was having trouble breathing (I had presumed covid early on, before tests were readily available, and ended up with pneumonia and a worsening of my asthma) and breath was charged in so many other ways then, too…With an airborne virus, of course, a breath can kill a person; also, the phrase “I can’t breathe” (among George Floyd’s last words) was used on signs and in chants during BLM actions, and then grossly co-opted by the anti-mask contingent. I was hyper-aware of breath, in general, and started to think about the breath that ran through my writing, the inhales and exhales on the page. It felt like a meaningful way to organize the collection.

Vered: Yes, the word breath now sounds an alarm for us all. It is fascinating to press rewind and look at the threads that weave themselves into our work. And to think about the initial glimmer that caught our attention and motivated us to write. Your essay “Room 205” takes its title from the fact that four of the care facility rooms where your father lived near the end of his life were numbered 205. How did you arrive at the structure of using 205-word flashes and what were the benefits and challenges of using this word-count constraint?

Brandeis: I tried to write this essay in a couple of different ways before I lit upon this constraint, first as a more straightforward narrative essay, and then as a more segmented, collage-style essay, and neither approach really worked—both felt too flat and long and unsatisfying to me. I set the idea aside, knowing I wanted to return to it, and at some point, I was struck out of the blue with an epiphany to write it in 205-word flashes. It felt like just what I needed to bring the essay to life; I loved marrying the form and content this way. I was able to recycle some of the collage-form essay—some parts needed expanding, and other parts cutting, plus I thought of new areas to explore, and it became a fun puzzle to craft each section into 205 words. A formal constraint like this can paradoxically be freeing, because the conscious part of the brain is focused on the form, and it allows surprising stuff to bubble up from the unconscious—-this happens with formal poetry, too (I don’t write a lot of formal poetry, but have played with the sestina quite a bit, along with other forms, and love how constraint can lead to some refreshingly weird and unguarded material.) Sometimes I felt like I had to be a bit of a contortionist to fit inside each box, so that was definitely a challenge, but it was a fun challenge, all that twisting and compressing. Constraints can also feel comforting and safe and did in this case—I felt like the form was holding me as I delved back into the experience of losing my beloved dad.

Vered: In an interview I did with Jeannine Ouellette last year we spoke about the use of literary constraints. She said, “The idea is, limitations can jostle us out of familiarity and into new territory, propel us away from our usual creative stomping grounds.” She quoted Joy Williams who said, “The moment a writer knows how to achieve a certain effect, the method must be abandoned. Effects repeated become false, mannered.” Can you talk more about how as writers we can break out of our own patterns?

Brandeis: I totally agree with the wonderful Jeannine Ouellette that limitations can jostle us out of familiarity and into new territory. I’m not sure I fully agree with Joy Williams that we need to abandon methods once we’ve learned how to use them, though (as much as I love Williams, and as much as I find this quote provocative.) We often return to forms because they work for us—poets like to return to the sonnet form because they find it endlessly fruitful, for example—and sometimes those forms are right for more than one piece. As I was putting my collection together, part of me worried that I was being redundant in my return to certain forms (the braided essay, the collage), but I also know those forms felt right for the subject matter at hand each time I used them, the way a sestina or villanelle feels right for certain subjects. I do think it’s important to guard against complacency in our work, so it’s always good to question our own approaches, play with new possibilities, and do what we can to knock ourselves out of our own ruts, if they are in fact ruts. I’ve been working on a craft book called Write Like an Animal (one I’ve wanted to write ever since I finished my craft book Fruitflesh: Seeds of Inspiration for Women Who Write, in 2002), and wrote about the difference between habitual patterning and instinctual return. I’ll share the gist of that here.

Caged animals often develop habitual behavior—they obsessively lick the bars of their cages or pace back and forth, back and forth, repetitive movements that make their captivity more tolerable. Sometimes when we return to the same subject matter or form, we are doing the same—we have become accustomed to licking those bars and don’t know what else to do.

Migratory birds, on the other hand, return to the same place every year because it’s hardwired into them; their bodies know what they need, know where to find the right temperature, the right food during the right season. If this is what you are doing as a writer, keep doing it, keep listening to that internal compass that tells you where and how to fly. And if you realize you have fallen into habitual writing, we’re lucky that unlike animals at the zoo, we have the keys to our own cage—we can try playing with a different form, using a different POV, a different verb tense, starting in a different place, etc.

Vered: In the essay “Thunder,Thighs,” a clever and all-too-true commentary about thigh anxiety, you triple braid a cultural history of women’s thighs, with your own experience, with survey answers you received from a surprisingly large group of women you asked about their relationship with their thighs. Can you talk more about the three braids of this essay and how they came together?

Brandeis: Years ago, I decided I wanted to write a book that explored the cultural history of the thigh as a way of trying to make peace with my own thighs. I started researching the way thighs have been viewed by different cultures throughout history and realized it would be good to have a contemporary look at how women feel about their thighs, so I put together a questionnaire asking everything from whether participants thought about their thighs during sex to what their thighs would say if they could talk. This was pre-social media, but I was active on a couple of discussion boards, and posted my call for participants there, in addition to directly asking friends if they wanted to participate. I was quickly flooded with interest–the topic had clearly hit a nerve–and I was so moved by the responses that poured in. As passionate as I was about the project, though, other projects became more pressing, and the book idea ended up on the back burner. Then I happened upon the research and questionnaires during a move and realized that I didn’t need to write a book on the subject—I could write an essay, instead. The only part that was missing was me, and my relationship with my thighs, which was the impetus for the whole project to begin with. I started writing all my thigh-based memories, and did a bit more research, and eventually had to figure out how to braid everything together. That part was fun, deciding which questionnaire responses and bits of research and my personal stories were most illuminating and interesting, and exploring how those pieces could speak to one another. Once I had a weave that felt right, I still wasn’t quite sure how to end the piece, but then an image flashed into my mind of a kick line, all the questionnaire participants and other women identifying and nonbinary people who had a complicated relationship with their thighs dancing in whatever way their bodies allowed, celebrating all our thighs together, and I knew I had found my ending. That image still gives me great joy.

Vered: The can-can image sure brought a smile to my face, and –oh, yes—the realization that not every idea has to become a book. Your essay “Spelling” opens with, “When Jewish children begin to study Torah, rabbis will sometimes give them a spoonful of honey so they’ll always associate learning with sweetness.” I happen to be dipping my toe into Torah study for the first time in my life. Have you studied what is referred to as the Pardes method or how to look at the layers of meaning in the text—the literal, allegorical, metaphorical, and esoteric? To me, it is exactly what I do with my memoir students. How do you describe your Jewish background and Torah study?

Brandeis: I grew up in a very secular Jewish home and am finding my way into a new relationship with my heritage as an adult. I remember my beloved philosophy teacher in high school saying, “You can find whatever you’re looking for in your own tradition,” and I didn’t believe her at the time, but of course she was right. Mysticism, earthiness, folktales, close reading of text—it’s all there. I haven’t officially studied the Pardes method, but I’d like to; it’s so resonant with how I teach, as well, looking at the various layers of a piece of writing—how it’s working on both a story level and a language level, what’s been left unsaid, what meaning we can take from the piece.

Vered: In the essay “Figures,” you write, in reference to the surface of your childhood ice skating rink “… some divots and scratches are too deep to fill, some bumps too tenacious to shave.” The essay ends with this prayerful sentence: “I can feel myself there again on the doomed rink of my childhood, cold air in my lungs, making circle after patient circle, leaving a mark so faint you’d have to kneel to know it was there.” Can you talk about the contrast between the deep divots and faint marks in your writing life?

Brandeis: What an amazing question—thank you so much! I could see interpreting this in a few different ways, but here’s what feels most true to me in the moment: the deep divots are the subjects I keep needing to return to in my writing (primarily, my mom; I thought I had exhausted writing about her with The Art of Misdiagnosis, but clearly that wasn’t the case; those divots keep reasserting themselves on the page!) and the faint marks are the images and scenes I can glide through without ripping my own heart out. That speaks to the inner experience of writing; in an outer way, I know my writing will only leave the faintest of marks in the big scheme of things—I don’t anticipate carving a big divot into the world, which is fine with me—but the act of tracing those patient circles is so satisfying (and yes, prayerful) in itself, and I’m so grateful to anyone who takes the time to kneel down and see them.

Vered: I love this answer. In The Art of Misdiagnosis, the book you wrote after your mother’s suicide, you quote the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, “What is the course of suffering? It lies in the fact that we hesitated to speak. It was born the moment we accumulated silent things within us.” In this book, you describe the moment in the garage with your mother that you began to accumulate silent things. To what extent and in what way is memoir an antidote to this universal human experience of suffering in silence?

Brandeis: I think all writing is ultimately a protest against silence, perhaps especially memoir. I love thinking of memoir as an antidote to suffering in silence—it can certainly be life saving for us to write about our experience, to break our own silences, and it can be life saving for readers who are feeling alone and need the lifeline of another person’s voice. I know books have been that lifeline for me—when I was in the deepest thicket of grief after my mom’s death, memoirs about suicide loss, like Joan Wickersham’s The Suicide Index, helped me find my way forward, and ultimately gave me courage to tell my own story. It’s so easy to go through the day only seeing the surface of other people; memoir helps us remember we all have complicated inner lives, and we’re all carrying more stories under our skin than the surface could ever show. Memoir helps us access and honor our shared humanity.

Vered: I can only imagine how hard it was to pick up a pen and write about your mother’s mental illness and suicide, especially right after the birth of your own child. How did the coincidence of these two life events shape your writing?

Brandeis: Both birth and grief can create gaps in our memory, so that convergence of death/birth was a double whammy for my brain. I’m grateful that some part of me knew to take notes throughout my mother’s disappearance, and in the early days after we got the news of her suicide—I don’t think I knew, at least not consciously, about the neurological impact of birth and grief, but the writer part of me somehow knew to pay attention, to capture the details before they melted away. I’d journaled in high school and college but had fallen away from that practice, and I’m grateful I trusted the instinct to jot things down in the moment. It took a while—about a year and a half—to be able to write about my mom after her death—and the notes I scrawled during that time period helped to fill, or at least bridge, the chasms in my memory. Being smack in the middle of birth and death was intense and humbling and discombobulating, and I think the experience pushed me to be braver in my writing, to go to harder places and take more creative risks.

Vered: I’m glad you brought this up. I often talk to my students about taking notes when they are in the middle of a traumatic life event. While it’s nearly impossible to craft a narrative when you are in the throes of a life changing event, if you don’t get the facts down you risk losing memory of salient, story-building details. But how do we take those notes and construct a story? Can you give us some insight into how this process goes for you?

Brandeis: I tend to write in scenes—I’ll write scenes and moments and details as they occur to me (or as I flesh them out from a notebook), and only later figure out how to string them together. It’s like I’m building little steppingstones and those lead to other steppingstones, and a path eventually gets built that way (sometimes with big gaps that I later need to fill in). Of course, sometimes I have little steppingstones all over the place, and can’t figure out how to tie them together into a cohesive pathway. When that’s the case, I like to make a list of all the scenes and figure out how (and if) they fit together, how they can be moved around into an order that makes sense, and what other steppingstones or other structures need to be built (and what needs to be pared away) to make the path clear.

Vered: Pam Houston refers to these moments of inspiration that lead to scenes as glimmers. I’m intrigued by how we all have metaphors for talking about our process, from first draft to completion. I’m not a painter myself but like to compare writing to the layers of an oil painting, from composition to pencil sketch to final layers and touch up. It’s so visual, it helps me shape a story. There is also what Donald Quist refers to as molding clay and you talk about steppingstones and structures. Allison Hong Merrill told me about Shannon Hale, author of The Goose Girl—who said, “I’m writing a first draft and reminding myself that I’m simply shoveling sand into a box so that later I can build castles.” How elegant is that? Following this train of thought, how do we as writers decide which sand is castle-worthy and which sand should be left on the beach?

Brandeis: I love all of these images—glimmers really does feel perfect for those moments of inspiration; it makes me think of bower birds finding shimmery items they love to decorate their nests. The painting image feels perfect, too—moving from a bare sketch to something layered and textured and colorful. And the clay and the box of sand speak to me so much, too. They make me think about Anne Lamott’s “shitty first drafts”—when we’re drafting, we’re compiling material, and it’s so much easier to later build something beautiful from a mess of clay or a box heaped with sand than it is to build something out of thin air. We create the building materials we need, and then we refine what we build with them.

As for knowing what sand is castle worthy, and what to leave on the beach, I think it comes down to our intention for the castle. What story do we want to tell with the castle and what kind of impact do we want it to have? Whatever doesn’t serve that intention can go back to the beach, even if it’s the most beautiful part of the castle (and of course we can always save those beautiful parts to build something else later).

After The Art of Misdiagnosis found a home at Beacon Press, my editor asked me to cut 5k to 7k words to make it more affordable to print. At first, this task seemed impossible, since each word felt so hard won. Once I looked at the manuscript, though, having taken some time away from it (which is always so clarifying), I realized how much didn’t need to be part of the memoir. I had thought the book was about me, about my breaking of my own silences, but I realized no, the book is about me and my mom and my attempt to make peace with our relationship and her suicide. Anything that didn’t serve that could go. I ended up easily cutting 20k words, a full quarter of the manuscript. That’s a lot of sand to throw back on the beach, but it made sense to do so, and made the castle of the book tighter and stronger. The discarded sand wasn’t a waste of time—I learned a lot from building with it, and it took me where I needed to go.

Vered: Annie Ernaux calls herself an ethnologist of herself. She writes, “I started to make a literary being of myself, someone who lives as if her experiences were to be written down someday.” Do you relate to this? I also heard her say, “To write is to fight forgetting. To write is looking for what I don’t even know myself before I write it.” Does this resonate for you?

Brandeis: Both of these quotes resonate for me, and in such different ways. I find that living as if my experiences are to be written down someday is not always a good thing—sometimes this leads to a kind of disassociation, where I’m narrating my life inside myself as it’s happening, and that removes me from the direct experience and makes me feel distant from my own body. Other times, it’s a wonderful thing—it can drive me more fully into the moment and make me feel more fully alive in my body because I want to take it all in, knowing I may write about it later (but also just wanting to immerse myself in the experience.) And the prospect of writing can help me be more brave, get out of my comfort zone…for instance, I was super shy as a kid, but put together a little neighborhood newspaper, and found I could talk to my neighbors if it was in service of the paper, even though I was too bashful to speak with them otherwise. Later, when I took my daughter to an audition for Annie Get Your Gun, and the assistant director encouraged me to audition, too, at first I said no, because I wasn’t an actor or singer, but then I thought about how I could write about that out-of-character audition experience, so I threw myself into it and much to my shock ended up with the lead role (and later ended up marrying my co-star!)

The second quote rings true in my bones. Writing definitely helps me remember, and I learn so much about myself and my life by writing; it helps me access some knowing part of myself that I can’t access otherwise. That quote reminds me of this famous quote from Joan Didion, which also rings very true to me: “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.”

Vered: The story of your marriage sounds like a terrific book! One of my students recently shared a breath-related writing rubric with me: “Try to end on an inhale not an exhale.” To me, this is about allowing the reader the final interpretation. What does this mean to you? How do you think about endings? Any sage advice?

Brandeis: This is such an intriguing, beautiful sentence—thank you for sharing it with me. The thought of ending with an inhale (not necessarily on the page, just in general) makes me feel a little claustrophobic and dizzy in my body, like I’ll pass out if I can’t complete that breath, but I love your interpretation here, how ending on an inhale lets readers complete the breath, themselves, absorbing the oxygen they need from the essay and letting the rest go. I definitely want each reader to leave each essay with their own unique experience of it. I’m not sure I have any sage advice for endings, since each piece of writing seems to demand its own particular way to end—some want to end with a strong sensory image, while others are better served with a more meditative ending, etc. Sometimes I write past my own endings, and only discover this during revision, when I see I’ve over-explained things at the end or had hit a potent image and then let that energy dissipate by going beyond it.

I’d say the most profound experience I’ve had writing an ending was with “Get Me Away From Here, I’m Dying.” I’d thought the two parts of the essay were connected only via the song the essay takes its title from, the Belle & Sebastian song that figured into both scenes explored in the essay (the last holiday before I left my first marriage and my last night with my mother). Then the final sentence poured out of my fingers, and I burst into tears; I hadn’t known what the essay was really about until I wrote that sentence “I lift my shirt, and he latches on, and I am all tears and milk and sweet, deep ache, alive with the mothers I’ve lost.” (a good example of how my writing knows much more than I do!)

Vered: I can’t let that go by without quoting Robert Frost: “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader.” What a profound truth he told so many years ago! How do we best maintain that element of surprise as writers so that we bring ourselves to tears as we write?

Brandeis: Surprise is one of my absolute favorite parts of the writing process—surprise and the discovery and emotion that can arise from that surprise. I think I create space for this by trusting the writing process, getting out of my own way so the writing can take me where it needs to go. Keeping my fingers moving and allowing associations to flow out. Letting go of expectation about what the piece should be lets the writing become its true self, lets it breathe on its own. In revision, I am fully intentional and focused on craft, but in the drafting stage, I surrender to the writing and let it have its own way.

Vered: Yep, as Stephen King says, the book really is the boss. It feels to me like I could open Drawing Breath to any page and find a message that is relevant to what I am experiencing and that will enrich my life. What goes into writing such a message-rich book?

Brandeis: Oh wow—that is amazing to hear; thank you! I love doing that kind of bibliomancy, opening a book at random and finding what I need in that moment, and it delights me you feel you could do that with my book. I hadn’t consciously set out to write a book full of messages, but I began most of these essays with the intent of sifting through something, of asking questions, and that often takes me to a place of contextualization and sense-making for myself, so I can see how that could translate into messages. I definitely don’t claim to offer answers for anyone, but if my grappling can be illuminating for others along their own journeys, how lovely!

Vered: Can you describe the struggles you faced while writing the book? How did you deal with them?

Brandeis: Because these essays were written over the course of 20 years, so many different struggles have been woven into them. Lots of self-doubt. Lots of fear about revisiting and reopening wounds. Lots of fear of putting vulnerable work in the world. When I was younger, I somehow believed that once I became a published writer, my self-doubt would disappear. This did not happen, but I *have* gotten better at handling the self-doubt, at knowing that I can make my work better with revision, at knowing I don’t have to be “perfect.” At knowing I’ll never be perfect, and that’s a good thing; I want to let my messy humanity shine through my writing. I’ve developed tools to deal with revisiting/reopening wounds over time, most of which deal with re-grounding myself in my body, reminding myself that I’m here and safe and not in the midst of trauma, even if my nervous system believes I am. It’s still scary to put vulnerable work in the world, but the generous, moving responses I’ve received when I’ve done so before remind me it’s worth it. I’ll often return to this poem by Sean Thomas Dougherty to shore myself up:

Why Bother?

Because right now there is someone

Out there with

a wound in the exact shape

of your words.

Vered: What a perfect companion poem for memoirists. I’m going to plaster this on my forehead and share it with all my students. While we’re referencing other writers, I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask you about authors that have most influenced you. Can you name three and tell us why?

Brandeis: Oh my goodness, how do I only pick three? I’ve been influenced by so many authors (and will continue to be influenced by the amazing people I read.) I’ll share the first three that spring to mind and will try not to feel guilty about not mentioning scores of other writers who have profoundly shaped me.

Audre Lorde was a shining light for me as I wrote my memoir (and is still a shining light for me). Her words “Your silence will not protect you” guided me through the most challenging swaths of that book. I love how she wrote about the life of the body and the mind in her poetry and prose, with deep exploration of her own experience and also of the larger political story. Sister Outsider and The Cancer Journals had profound impacts upon me and continue to nudge me to write through fear.

I met Laraine Herring when we were getting our MFAs at Antioch University over twenty years ago, and we’ve shared work and supported one another ever since. She is constantly pushing her own creative envelope and inspires me to push my own. Her latest book, A Constellation of Ghosts: A Speculative Memoir with Ravens, is astonishingly gorgeous, and broke open possibilities for me (and for so many others) about what nonfiction can be and do. I can’t imagine my writing life without her.

I’ll also name a more recent influence, Diana Khoi Nguyen, whose poetry collection Ghost Of was a revelation for me. She writes about suicide loss, too—the loss of her brother—and her use of visual poetry and other imagery made me want to be more visual in my own work.

Vered: What riddle are you trying to solve?

Brandeis: How to be as alive and awake and generous as I can muster during my short time on this earth. How to be free.

Vered: Speaking of generosity, thank you so much for taking the time to wonder/wander with me. I have learned so much about you and your art.

Brandeis: Thank you so much. It’s been a true pleasure (and so illuminating) to have this conversation. Thank you for all of your rich, thoughtful questions!

MEGAN VERED is an essayist and literary hostess. Her essays and interviews have been published in The Linden Review, High Country News, Shondaland, Kveller, The Rumpus, the Maine Review, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and the Writer’s Chronicle, among others. Her essay Requiem for a Lost Organ was long listed for the Disquiet 2022 Literary Prize, and she was a finalist for the Bellingham Review’s 2021 Annie Dillard Award for Creative Nonfiction. Her essay, How a Bar of Soap Taught Me To Apologize, went viral on Flipboard’s 10 For Today. Megan lives in Marin County, where she leads local and international writing workshops and participates in literary readings. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts, heads the governance committee for Heyday Books, and is the CNF interviewer for the Maine Review.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories, sports musings, or book reviews sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

NEW book release

Ghosts Caught on Film by Barrett Bowlin. Order the book of which Dan Chaon says “is a thrilling first collection that marks a beginning for a major talent.”

GET THE BOOK