Tall on the Scriptures and short on trust, folks in these parts agree about the primordial and problematic difference of outsiders. Citing Genesis 11: 6, Bible readers fear Nothing they plan to do will be impossible. This the prequel to the Tower of Babel, and folks fret about the sequel. They’re talking about outside agitators, and I fear they may be right.

Our community boasts a one motor lodge, The Saving Grace Motel, and a run-down high school. The local mascot is the bumblebee and, believe me, the town is abuzz with everybody’s beeswax. Folks mind each other’s business as allegiance to the Flag, obedience to the hive norm. Everybody knows how to honey the clay. The sins of the fathers and, we might add, the mothers, visit the children. Therefore, they begrudge outsiders space for Saving Grace. No vacancy. No room in the ark.

From somewhere else, parts unknown, Ashford and his sister were better-than-average students. Middling athletes on a town where hitting a ball with a bat or a racket meant something, they were blow-ins, children of parents lost in life’s shuffle. Iris was a stunning blonde with eyes so green they seemed plucked from a meadow. Handsome Ashford was dark-haired with an olive complexion. At school, kids tagged him a sea nigger.

Ashford was too smart to fight back with his fists. His people, he claimed, were Italian merchants who settled Mobile Bay under one of the seven flags. That data changed his status to burnt pizza, and, by senior year, bullies degraded his fine name to Ash. As in over.

Babysitting and mowing lawns, the two teens made do in a battered trailer. No one suggested college, and high-school graduation marked the end of the duo’s formal education. Their recess time was over.

The church crowd still debates which came first, his seizures or her amputation at the knee. Both happened around the town’s Easter egg hunt. Did the sister’s road accident trigger Ashford’s panic attacks? Or, did the brother’s seizures drive pretty Iris into the fast lane on a late-night joyride?

Town folk weary of compassion. They also are wary of too many Sunday sermon feelings creeping into the weekdays like kudzu. Big experts on sloth, they attribute Ash’s tremble to in-born laziness. Despite his Italian blood, he’s too wavy to work pizza ovens. Scary when that boy plays possum. Sets the dogs to barking, like he’s dead as Lazarus, spooked out and white, ready for maggots. And then come back to life, stealing the show at inconvenient moments, like when the Masons parade on lawnmowers or during said Easter egg hunt.

Iris, around town on her prosthesis, causes more distress. People don’t praise her courage. Big experts on neighborly love, they resent her because she’s an unwed mother. Peg-leg, be gone, and take your biddy with you, they say, stirring sugar in their coffee.

Not that their pregnant teens are married. But that’s a different story, and there always is a story. The accident that cost Iris a leg landed one of their boys in the slammer, behind bars on a DUI turned hit-and-run. In the Big House. For years. Leaving his toddlers to grow up without a daddy. Sad what the lost leg of a girl from somewhere else does to a local family.

Meaning, the familiar fallout: grandparents stuck with a pack of ornery young’uns and a growing stack of bills. Soon granny and poppa, strapped for cash, peddle painkillers. They know better. Nothing major, mind you, just enough to get by and honey the clay.

Then they’re taking. Nothing major, mind you, not smashed, just enough crank to load the brats, unload the groceries, strip the beds, haul the laundry, roll up the rugs, wash down the shower stall. Their backs are killing them, and now they’re addicts. Nothing major, mind you, just a couple of hits to rest, maybe set the room on fire.

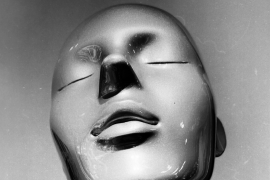

Ash, increasingly fearful of backlash, sleeps in a handyman’s toolshed among rake, shovel, and leaf blower. Or, so I’m told. Thinking safety in numbers, he’s shaved his head and acquired an inked neck mural twice as wide as a clerical collar. The ring of tattoos makes his skinhead look like an afterthought—a boiled egg in an eggcup. In black denim and biker chains, the guy clanks as he walks. Downright spooky.

And this is where the grapevine goes beserkers. Ash clanks full-chain into the Dollar Store, buys a big bunch of artificial flowers, flirts with the associate manager, and, bouquet and chains, he and the redhead hook up. She’s in her late thirties, and he, a house partner of sorts, makes the coffee, feeds the fish, and, clank, clank, escorts her school-age kids to and from the trailer park bus stop. Safety first, clank, clank, but her children hate him because he sleeps where they used to. In mommy’s bed.

Did his sister’s accident push him into the arms of an older woman? The redhead also had fostered a high-school drop-out. For three years, she received $429 a month for his care. Taxpayer supported dollars, but okay. She eased Ash in as the foster child aged out of the system. Not good news.

The foster boy has oral cancer. He’s losing part of his tongue. No one blames Ash for this travesty, but they regroup on the news the State will pay for the cancer operation in Jacksonville.

Let foster boy stay there, all agree, hustling on them mean city streets. Better there than here, they say. Roll up the welcome mat. No one wants the boy whore back in town. What nasty might he drag in?

More to the point, they wonder if Ashley will lose his tongue, maybe swallow it in a nervous fit. Nothing personal, mind you, but maybe the redhead is gold-bricking, biding her time, looking for a better man at Dollar General.

Iris, meanwhile, goes dancing on her fake leg, a shiny metal bar with a cute pointed foot, something like a travel iron. At the Fourth of July fireworks display, she meets an Army Ranger who served in Iran. Wounded in action, he admires her grit and gorgeous green eyes. An item, they marry at the church. Big wedding, real nice—white lace, best man, bridesmaid, and rice. The Saving Grace Motel is full up with guests, men and women, right proud in dress uniform. Makes us right proud. Now, Iris is expecting. Her little daughter will have a sibling. Happily ever after.

People accommodate Iris because her husband, one of the boys from one town over, is a warrior. Keeping him in the community is a big upgrade from the lewd drunk driver in prison. Gossips reason Iris paid for her nice husband with her leg. Good thing she didn’t lose an eye, they concur.

That mean, they try to imagine Iris as a one-eyed gal with two good legs. Like before. They cud on this thought. They like to be thinking of the warrior wed to one of their mud-eyed girls and a daddy to the kids.

Trade-offs are part of life, and, soon enough, clank, clank, Ash and his chain links are back in the handyman’s toolshed keeping company with rake, shovel, and leaf-blower. No wedding, no rice for him. Collecting trash, a good thing, he ekes out a living in the recycle trade. Mornings, he strips busted AC units for the copper wire. Afternoons, he sorts scrap metal in a yard sky-high with junk, appliances mostly and automotive.

Some say the redhead threw Ashford out because she was jealous of Iris. If she, an associate store manager with two good legs, can’t have an Army hero, Ash can’t have her. Her home, her rules. No blowback.

Unless Ash swallows his tongue for a high-money operation and out-patient care.

Others blame love strange as a low-hanging fruit. They say the foster boy toxified part of the red-haired woman’s heart like the cancer toxified part of his tongue. Like shaking hands, a deal done with the Devil.

You go figure.

Morning regulars at the beauty parlor, the coffee shop, or the post office love talk, the bigger the story, the better. But big mysteries have no purchase in a small town. People cut them down to scale. That’s why I’m thinking Iris lost her leg. Forget the fatted calf and golden idols. Around here, folks need real live scapegoats to explain things, to downsize them for small hearts and peanut brains.

But trash tattles, and God frowns. That’s why Ashford, clank, clank, recycles piled-up bent fenders and broke refrigerators with the doors removed. Make no mistake. In the junkyard, the kid talks to the Lord.

Look for yourself, more like, listen for yourself. Never mind what the neighbors mumble about outsider agitation. Be careful. Ash is building a Tower of Babel.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories, sports musings, or book reviews sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

NEW book release

Direct Connection by Laura Farmer. Order the book of stories of which Mike Meginnis says there is “an admirable simplicity at their heart: an absolute, unwavering confidence in the necessity of loving other people.”

GET THE BOOK