Some time in the late seventies, when Iraq was flourishing, we bought our first television. Some other families we knew already had a TV, other uncles who worked at Mosul University, or as doctors at the hospital in Mosul or as engineers at the refinery.

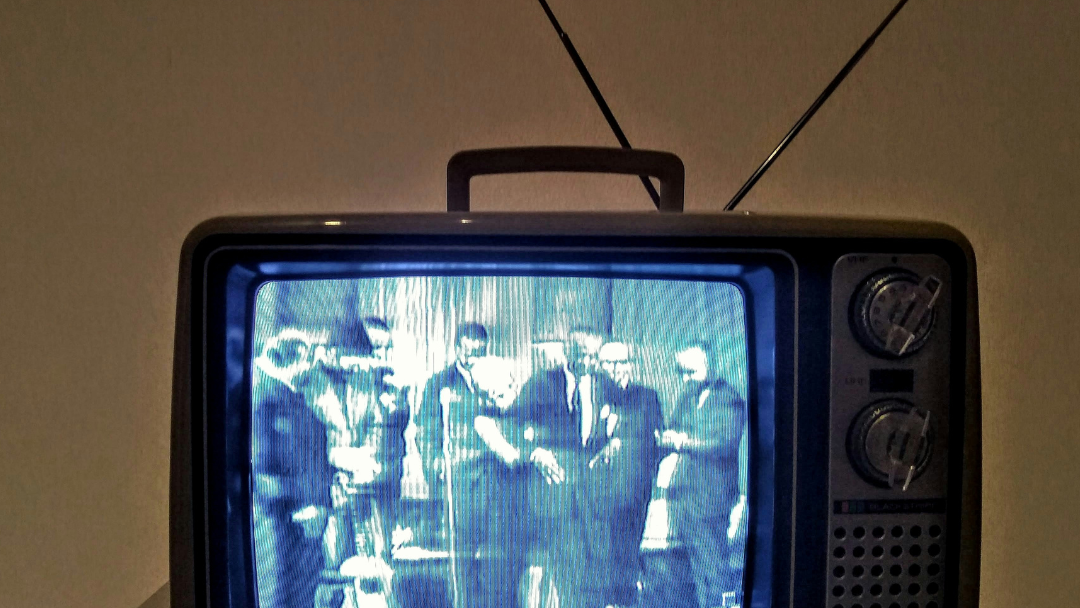

It was a black and white box with an antenna. My father started to assemble it in the evening. I remember watching him, as if the business of setting up the television was itself an entertainment. My mother must have given me dinner right on front of the TV that evening, in that room. I remember the room– double height ceiling–, under the stars that led up to the second floor bedrooms and the roof, the kitchen in front, the bedroom to one side, the back garden, and the living room at the front of the house, a space connecting all the spaces in the house.

I learned to sweep the floor in that room, my mother or my father teaching me how to do it methodically, first one line and then another. The bedroom to the side was where we slept in the winter, all huddled together on two big beds pushed next to each other with a heater going, and where I punished my two younger brothers, making them stand facing the wall if they did anything to displease me. There was a mirror attached to an armoire in the bedroom where I first looked upon my tight curls and cried for the straight, long hair of other girls.

I read a lot of American and British books in that house, Archie comics among them, that another auntie’s sons–who attended a boarding school in England–brought home with them to read in the summer. When they left, the auntie would give my mother all these books, stacks and stacks, that eventually filled an outer room adjected to the front verandah, which was crowded with piles of books reaching from the floor to the windows. There were some places in Mosul, like the hospital, where you could buy American and British books for children, where my mother went hunting for books for me regularly. She also checked out English books and magazines at the library, or at local shops that imported these. I cut my teeth on the romantic stories in these magazines, wholly inappropriate for my age.

That night, I finished my dinner and still sat, watching my father as he tried to make the antenna work. There were whirring noises, then the screen would burst into life in a blaze of dots, but no pictures appeared. You ask how we looked. My mother would have been wearing a sari, long hair tied in a loose braid, glasses on her eyes. My dinner would have been Bangladeshi food, rice and chicken and ripe Iraqi tomatoes. My father would have been wearing work clothes, shirt sleeves rolled up, dress pants. He had a mustache and a full head of thick hair. His students came to visit in this house–and once, a student’s mother, bearing a basket of freshly baked klecha, an Iraqi pastry filled with pummeled dates. Later, her son went to fight in the Iraq-Iran war in the eighties as part of Iraq’s volunteer army.

Finally, after watching my father struggle to get reception, my mother said I had to go to bed. I had school the next day. Or perhaps the television did work before my bedtime, but I have no memory of what I watched. She had me brush my teeth at the sink that also led off from that central room. The sink was in front of a bathroom that had to be heated by a boiler. The shelf above the sink held the hair cream Brylcreem and other Western products left by the men who used to be tenants in the house before us, renting from our Iraqi landlord Mal Allah. I went to bed full of regrets and jealousy for the show my parents would watch without me, as the Iraqi TV would air Little House on the Praire at eleven o’clock that night. I fell asleep feverish with desire to watch this American TV show and frustration that it was past my bedtime.

The next morning, my father lit the heater, a cylindrical metal contraption that ran on kerosene. I jumped out from the warm bed directly into the aura of heat emanating from the kerosene heater. As my mom got me ready in the kitchen, tying my hair in two pigtails, she told me all about the American show they had watched, Little House on the Prairie, a show about an American pioneer family that I had watched a few times in other people’s houses. I listened, seeing the pictures in my eyes, vibrant as emerald green. The story my mother told me was about an episode in which Laura Ingalls ran in a race–perhaps she had to travel to another town to compete-, but she didn’t win the race. So Laura’s mother told her that it wasn’t important if she won or lost, as long as she had tried her best.

For the rest of the short time we stayed in Iraq, till the Iraq-Iran war broke out, that’s what we did every night. We watched American television in black and white, as did Iraqi families in their homes. Some of the shows I remember are Little House on the Prairie, Brady Bunch, Eight is Enough, and Big Valley. These were the shows that built our romantic image of a benevolent, warm-tinted America–of big, happy families and the wild west–, and our views of the world, our moral perception.

We left Iraq before the West imposed sanctions on Iraq so that they couldn’t sell their oil, before America bombed Iraq again and again. Then the Americans came and finished the job, destroying Iraq–the museums, the libraries, artefacts and antiquities, the stability, the safety, the warmth, and the homes with the American TV shows playing in living rooms, and the mothers and fathers who used to sit in these rooms, watching American television with their arms around their children.

GEMINI WAHHAJ’S novel Mad Man will be published in Fall 2023 by 7.13 Books. Shehas a PhD in creative writing from the University of Houston. She is Associate Professor of English at Lone Star College in Houston. Her short story collection Katy Family is a finalist for the Acacia Fiction Prize by Kallisto Gaia Press and her novel Mad Man was a finalist for the Big Moose Prize by Black Lawrence Press. Her short stories have been published or are forthcoming in Granta, Zone 3, Northwest Review, Cimarron Review, the Carolina Quarterly, Crab Orchard Review, Chattahoochee Review, Apogee, Silk Road, Night Train, Cleaver, Concho River Review, Scoundrel Time, Chicago Quarterly Review, Arkansas Review, Allium, Valley Voices, and other magazines. She has received the James A. Michener award for fiction at the University of Houston (judged by Claudia Rankine), an honorable mention in Atlantic student writer contest 2006, an honorable mention in Glimmer Train fiction contest Spring 2005, Zone 3 Literary Awards winner in 2021, and the prize for best undergraduate fiction at the University of Pennsylvania, judged by Philip Roth. An excerpt of her Young Adult manuscript The Girl Next Door was published in Exotic Gothic Volume 5 featuring Joyce Carol Oates. Formerly, she was senior editor at Feminist Economics and staff writer at the national newspaper The Daily Starin Bangladesh. She has edited articles for the Encyclopedia of Women in Islamic Countries and is editor in chief of Cat 5 Review, a magazine of writing by community college students. Currently, she serves as editorial staff at Guernica.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories, sports musings, or book reviews sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

NEW book release

Direct Connection by Laura Farmer. Order the book of stories of which Mike Meginnis says there is “an admirable simplicity at their heart: an absolute, unwavering confidence in the necessity of loving other people.”

GET THE BOOK