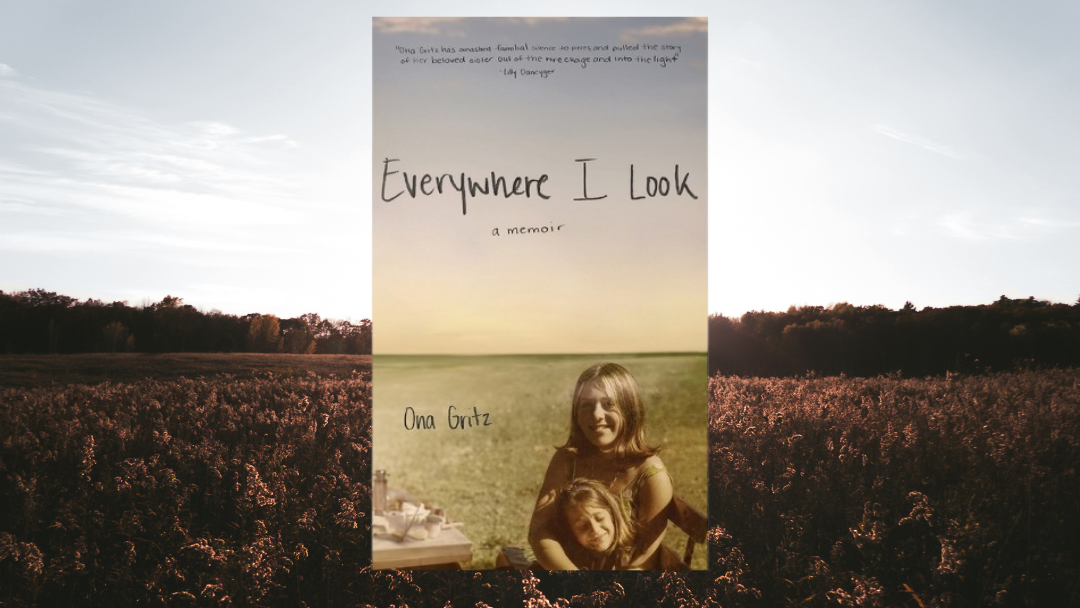

Ona Grtiz’s memoir, Everywhere I Look, is a vulnerable and emotion-filled tribute to her late sister Angie that dives deep into the many forms in which grief presents itself. Angie, the family’s black sheep, would run away often as a child because she didn’t feel like she fit within her family; and Gritz would be left behind wondering if or when her sister would ever return. Angie loved her sister and would always come back to her. Years later, Angie is married, pregnant, and has an infant son. After Angie goes missing again, Gritz believes this is just another one of Angie’s normal disappearances, but Angie doesn’t return.

Written as a letter addressed to Angie, Gritz writes this memoir through her grieving process after learning that Angie had been murdered by a family friend, and learns how to move on while carrying her sister with her. Discovering that people you once fully trusted have committed unspeakable acts against people you love is one of the most difficult things to learn to live with.

Though my experience with betrayal and grief differs greatly from Gritz’s, I saw myself and my own experiences while reading this memoir and was able to empathize with Ona’s circumstances while losing a sister and those whom she trusted. Over a series of emails, I had the good fortune to interview Gritz and dive deeper into the important themes and connotations of her memoir.

Gabby Trippi: In your memoir, Everywhere I Look, you write in the second person POV, as if you were writing a letter to your sister Angie. Was the goal of this to have the reader envision themselves in your sister’s shoes?

Ona Gritz: That’s such an interesting way to look at it, and now that you say it, it seems really logical. But what I envisioned when I made that choice was for the reader to be more in the position of listening in on an intimate exchange. Eavesdropping, but with an implicit invitation to do so. The idea to address the book to Angie came to me late in the process of writing it, as a way to get closer to the material. To get myself to open up more, and to be as honest as I could about who I was in the story of Angie’s life and, in turn, what it felt like to be me in our family. In talking to her, I allowed myself to feel my vulnerability and to confess things I’d never said aloud, the way I’d like to think I would if I were lucky enough to have the opportunity to talk to her again in life. All that said, I really like this other prospect of the reader feeling as though they’re in her skin, even if I hadn’t thought of it!

GT: What I loved most about your memoir was your honesty and vulnerability throughout. Grief is a hard subject to write about and revisit, and it takes a lot of bravery to write so candidly about such a complex topic. Was there a part of this story that you had to talk yourself into writing?

OG: Thank you for saying that. Those are the qualities that I love most in a memoir too–that feeling of being confided in, of being trusted with someone’s deepest truths and discoveries–so I’m really happy you see my book that way. One aspect of the story that I really dreaded delving into and admitting was not only how close I was to my mother, despite her harshness to her other children, but how dependent I let myself be on her, even as a teenager. There’s one passage in particular about how, before I left for college, she was still trimming my nails and tying my shoes. It was part of how she coddled me as her disabled daughter. And I think it’s a powerful moment in the book, where it sits in contrast to how my sister was left to fend for herself, but I dreaded putting it in there. In fact, I remember that when I read it to my husband, who’s often the first to hear my work, I worried that he’d think less of me.

GT: A significant repetition in your book is the sound of your mother’s “crisscross slap of her hands” after she realizes that your sister is truly dead. You continuously imagine this reaction from your mother and how it was as if your mother was wiping her hands clean of Angie forever. This repeated line perpetuates the ongoing theme that your relationship with your mother differed greatly from Angie’s relationship with her. How did the favoritism your mother cast upon you at an early age affect your relationship with Angie?

OG: I felt guilty about it for sure, but I also believed myself to be the good girl out of the two of us and the one more worthy of love and care. It’s so complicated because our parents define the world for us as children, and that is definitely the message I was given. Angie was given it too. So while we loved each other a lot, there were ways we’d each lash out as children. She’d do things to scare me or make me cry. I’d tattle on her or pester her to the point that she’d tattle on me, knowing my mom would take my side. Not long after she left home, which, as you know, was when we were both still really young, she stopped trusting me with her secrets, and I didn’t let myself wonder too much about her life or take in how hard things were for her. I felt culpable for her suffering because of that favoritism, which made it too hard to think about. I still adored her, but at the same time, I was shut off from her emotionally in significant ways. It stayed that way long past her death until I finally began to explore her life as I researched and wrote this book.

GT: You write about how grief comes in waves and has funny ways of sneaking up on you in small everyday moments. What have you learned about grief after all these years, and what, if anything, has grief taught you about yourself?

OG: For a long time, guilt and shame stood in front of my sorrow, blocking me from feeling it. I think that’s why it snuck up on me the way it did at times. I’d never let it pour out or over me, so it leaked out instead. And even when it didn’t, it still had its effect, a kind of low grade sadness or pallor that’s a part of who I am, even in my happiest moments. One thing I’ve learned is to not be hard on myself about it. There’s no right time to grieve or best way to do it. We all have different constitutions and internal clocks. We all have been hurt in different ways, so we respond to pain however we can manage at the time.

GT: Following up on that question, how did you deal with revisiting your grief while writing this book, and did it affect your writing process?

OG: I stopped to cry when I needed to. I also took long breaks and worked on other writing projects. But by putting me in touch with my grief, writing this book also put me back in touch with my love for my sister, brother-in-law, and nephew. Love and grief are so entwined and, because they are, there is beauty and pain in both. I got to live in that complexity as I wrote. I got to grieve over who I lost and what they each went through. It deepened the writing and helped me heal, even as it broke my heart.

GT: True crime shows and podcasts are having a moment. But there is also an ongoing debate that true crime media can be very exploitative. What is your opinion on true crime podcasts and media? Do you think they can be too exploitative?

OG: They certainly can be, depending on the tone and, above all, the intention. In the book, I describe a night I happened upon an article that listed the apartment where my sister and her family had been killed as a stop on a self-guided tour of “scary San Francisco.” It was treated like a joke and that really upset me. I’ve also come upon podcasts and shows that feel exploitative in that way, where a story of violence and tragedy is told for pure shock and entertainment value. But the other side of it is that we’re interested in the human experience. What happens to people? Why? Who have we lost to violence and what were they like? How do the people who loved them integrate that loss into their being and their lives? If a story is told with care and respect, it can be really moving and even helpful. In books like Sarah Perry’s After the Eclipse and Jane Bernstein’s Bereft, and podcasts like Death of an Artist and Criminal, I’ve read and heard things that have validated my feelings or helped me understand my experience in a new way.

GT: An extremely interesting stylistic choice you made in this memoir was revealing who the killers were on the very first page. What was your goal in exposing Angie’s murderers from the very beginning?

OG: This may sound contradictory, but it was actually a way to take the lens off of them. To get the whodunit aspect of the story out of the way rather than have it be the focal point it is in more traditional true crime tellings. That was how Angie died and it was awful, but she had a life before that, short as it was, and that’s what I was interested in exploring. Sharing how I remember her. Learning where she was and what she went through during the long stretches of time when we weren’t together. Uncovering why she was treated the way she was by our parents who were only ever loving to me. Turning the lens on myself to look at my role in that dynamic. And finally–here’s where the murder does come in–what was it about all this that pointed her toward danger?

GT: You shared that you were in college for writing, specifically poetry, when Angie, her husband Ray, and their child Ray Ray were murdered. Many of your poems in the following years were written about Angie and what she meant to you. Since these events unfolded, how has this trauma shaped your writing?

OG: In grad school and a few years beyond that, many of my poems were about Angie. But after that, I didn’t write about her for a really long time. I barely let myself think about her because of all the guilt and shame we spoke about earlier. But, of course, my feelings for her showed up on the page anyway. My first children’s book was about a girl separated from her family for the summer who longs to connect with another child on her block who, in turn, keeps her at bay because she doesn’t want to get close to someone who will be leaving in a few months. Then I wrote a chapbook of poems centered on the year I lost both my parents, and of course every grief contains all others. A book that came out last year, but that began long before I opened myself up to Angie again, is a children’s novel about a girl who longs for her older half-sister to live with her. Loss. Longing. Sisterhood. These are my themes as a writer and that has everything to do with Angie and the trauma of my loss, even if I wasn’t always conscious of it.

GT: A prominent theme in this memoir is the idea of sisterhood. You write about Angie, “My tormentor and my protector, the back and forth of it as dizzying as my ride on the swings.” As well as “My sister is fun and funny, I felt the story said. To me, you were the brightest light in our house.” From these lines, the reader can tell just how much your relationship with Angie meant to you. What does sisterhood mean to you now, and does it differ from the sense of sisterhood you experienced as a child?

OG: Here’s a way I’m still quite childish: I can get very jealous around sisters, especially those who have a close bond. In some ways, I guess I’m stuck there, as the kid sister of a runaway, longing to have her home and in my day-to-day life. What’s changed is that I now recognize that part of having a sister is being one. Ultimately, that’s what writing this book was about for me. There wasn’t much I could do for my sister in her lifetime. I was too young and there was too much I didn’t know or understand. But the one way I could be a sister to her now was to bear witness to her life and her death, then work to tell about it honestly and artfully to you.

GABRIELLA TRIPPI is a creative writing student at SUNY Oswego. She lives in Naples, New York and enjoys cuddling with her three dogs. Follow her journey on Instagram @gabriella.trippi.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories, sports musings, or book reviews sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

NEW book release

Direct Connection by Laura Farmer. Order the book of stories of which Mike Meginnis says there is “an admirable simplicity at their heart: an absolute, unwavering confidence in the necessity of loving other people.”

GET THE BOOK