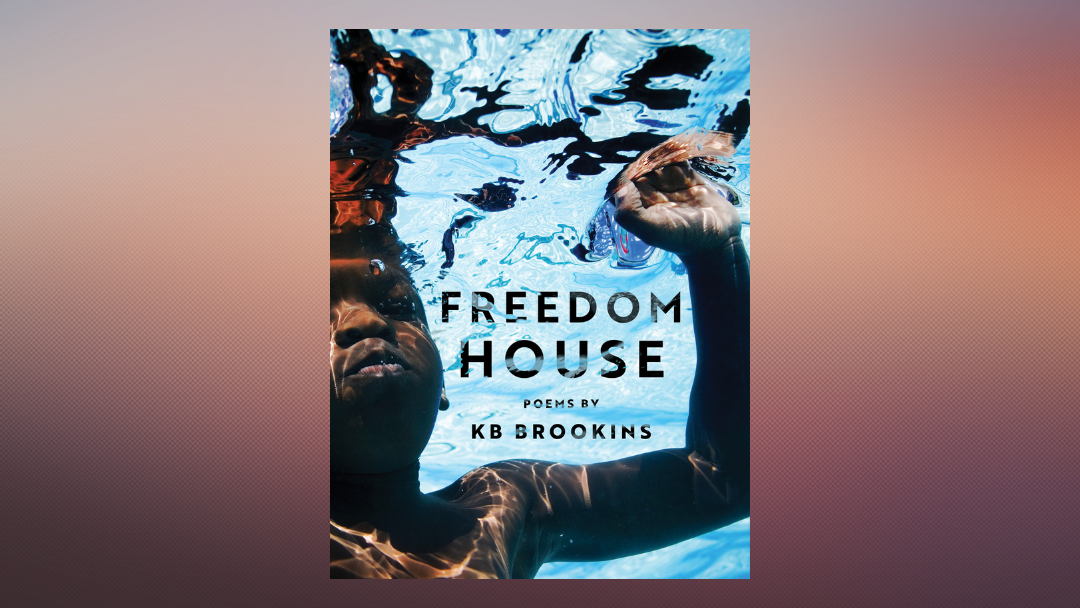

LO: I’m excited to chat about your new book that’s coming out, the full poetry collection, Freedom House. I just finished reading my copy of the manuscript and absolutely loved it. Let’s start off with learning a little about your journey as a writer.

KB: I’ve written diary-type journal entries since I was about seven, so I’ve been a writer in that way for a long time, as far as transcribing my thoughts into text. I heard a poem performed out loud, and a contemporary poem for the first time in seventh grade. Teachers really do make the world go ‘round, but I specifically remember my English teacher, Miss B Williams doing a dramatic performance of a poem written by one of the students in our class. For those three minutes, I was captivated by the way she was able to bring that student’s voice to life, and that always stuck with me and made me see poetry in a totally new light.

At one point, I went to an MFA program, and I didn’t end up finishing that program, but it showed me that there are multiple ways to be a writer. And I started being a writer mostly in what I would call spoken word or slam spaces. I moved to Austin in 2018 after I quit that MFA, and as soon as I got here, I asked, “Where are the bookstores? Where are the open mics? Where are the comedy shows?” I enjoy being around artists, not even just poets, but also musicians, photographers, and visual artists. That’s how I feel most at home since those are my first friend groups. And it’s always been my thing, doing the art thing with other people. And now people are more interested in the things I write.

LO: Yes, thank you for sharing that. You started young; I’m jealous! In another interview from your previous book, I believe that you attended an event at Malvern Books with local poet and writer ire’ne lara silva. You mentioned that she said in passing, “When you identify yourself with a wound,” and that phrase was an inspiration for you, and a jumping-off point for your chapbook with that title, which won the 2022 Saguaro Poetry Prize. That was fun for me to see because my poetry journey started at Malvern with a reading by ire’ne in 2018 where I learned that poetry was so much more than I had previously assumed. I would love to hear a little more about your inspirations, the people that you know, or other writers that help you keep going and learning and just enjoying the written word and everything that it can do.

KB: That changes as the days change. But I think a writer is as good as what they immerse themselves in. Your writing is reflective of your world, right? In addition to checking out the local bookstore scene in Austin, I’ve also had some of the best shows I’ve done be at places like drag shows, or variety shows where I’m on a lineup with a mix of people. I also love to just be a poet in places where people don’t expect poetry to live. A bar, or boxing ring, for example. If people are willing to listen, I will read.

Teaching is its own artform that you have to learn and refine over time. I think K-12 educators teach us a lot about creativity, and teachers are a big inspiration. I’m inspired by people using multiple art forms. I’ve been posting about inspirations that I’ve had for Freedom House, and it runs the gamut from other poets and writers in other genres, to podcasts, musicians, and comedians. Even if I’m not directly quoting the way they use rhetoric, I learn from it, like how in order to be funny, you have to say things in a certain way. You have to be able to put your sentences together. I think comedians are some of the smartest people and most artistic people because, how can you talk about something like capitalism and make it funny?

LO: So true; humor helps connect with a wider audience.

KB: It can be deep and dark topics like racism, but people in the audience are laughing. You have to be able to turn a phrase in a certain way, and when I see someone do something clever or fun, I then try to mimic that in my writing if I can.

LO: It’s great to hear how many sources of inspiration you pull from. Let’s dip into the manuscript. I feel like this collection starts off with fierce hope. The first poem is, “Black Life Circa 2029” where you envision liberation being just 10 years away from a traumatic experience you had with cops in 2019. My takeaway from that was that you have trust in the work that we’re doing and that it will get us the results that we need. Was that your intention with opening with this poem, or am I reading into that with too much of a positive lens?

KB: I want to give my answer with the asterisk of how I love anything that people take from my writing. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen when people are talking about other people’s writing in front of the writer, and it’s like, “Oh, you know you did this juxtaposition, and blah blah blah,” and the writer is just like, “I guess so.”?

LO: Yes! That definitely happens.

KB: One cool thing about publishing is that once it’s not just in your Google docs, it goes to live its own life, and people bring their own experiences to the poems, and I think that’s one of the main reasons why I publish. I get that my perspective is not the only perspective. So what I’m thinking about or what I initially was thinking about with that poem, yes, it was something traumatic that happened in 2019 in Austin, and I think we think of things like ‘defund the police’ or phrases like ‘abolition now’ so abstractly as if it’s a thing we want to happen in the distant future, but the distant future doesn’t have a specific year. I wanted to consider, “What do I believe in my heart of hearts could realistically happen in 10 years?” So I did a time jump to 10 years and wrote the opposite of what really happened in that interaction, and the opposite of what has happened to Black Americans throughout history.

I’m talking about those things in that poem and thinking about what kind of life I would like for myself and for other people like me. The next 10 years haven’t happened yet. So my goal, and really what I would love, among other things, is for someone to read this and feel galvanized to do something. Galvanized to take some kind of action. So what would actually need to happen in the next 10 years in order for the first two lines of that poem to be a reality? Or, what is the life that you would like to see in 10 years? And who knows, we couldn’t have seen 2023 this way in 2019, right? Things are so unpredictable in negative ways, but what if they were unpredictable in positive ways?

LO: Yes, I hope so. Especially in Texas.

KB: Yes. I’m interested in speculation, and talking about a future as if it could happen, since that would hopefully make us take the necessary steps to get it to happen.

LO: I love what you’re saying about how there could be positive surprises. We could be thinking in certain timelines about what abolition or liberation looks like, feels like, sounds like, and thinking about how we can start or continue building toward that. I appreciate how you dig into those ideas in this whole collection. And, I’m curious what your experiences have been in writing spaces as far as poems like the ones in this collection that are really bold and unapologetic.

KB: Right. It took a lot of poems of me being scared to be that way in order to get to those poems. And I actually am very grateful that I wasn’t in MFA walls while writing that book. But I just started a new MFA program in the fall of 2022, and if I feel like if I’m working on something, I have to avoid over-editing it. I have to just get it out first, turn off the editor in my brain and consider how much I have to say about that subject because I need to figure out if it’s a project, or if it’s just a series of poems, or just a current obsession that I would revisit later when I have more to say about it.

America expects you to be a certain type of Black writer, specifically a Black writer teaching non-Black people how to be better people. And it felt like the conversations I was trying to start felt a little bit more inter-communal. I want to speak directly to Black people and feel ok with that and know that it’s not going to get me a book deal with a top-five press, and be ok with that. I can’t change the fact that I’m Black and queer and trans, and I live in Texas, and that none of those things is the majority in the literary landscape. And if I want to talk about those things, I don’t want it to always be from the perspective of teaching someone about my body or teaching someone about how my mind works. I’m also disabled, and just in order to write this book, I had to rid myself of feeling scared that people won’t understand. One thing that makes poetry a unique form is that we’re willing to take risks with language that other forms are not willing to take. We can take that associative leap that you cannot take in a memoir, or even in a novel. Poems can do that, and people won’t feel so jarred by it. So I knew poetry was the form for this, and I also knew I needed to keep it in utero while I was writing it. I had to not be in an MFA program to write that book because I would have brought those poems to workshop, and would have felt worried about things like pushback. Freedom House is a project that doesn’t aim to make unobjectionable work. I can actually be in an MFA now that I’ve written that book, and now I feel more confident in that kind of voice that I’ve established.

LO: Yes, that makes sense. I noticed some fun forms you incorporated into this collection. You have a fantastic erasure that inspired me to try some more erasures. Unfortunately, Texas legislation provides so much opportunity for strong erasure poems. And also, you had a duplex, which you called a failed one in the title, but with the way you wrap it up at the end, I feel like it still honors that form created by Jericho Brown. I’d like to hear your thoughts on form and how it helps you or creates some challenges for you.

KB: Right. Form is one of my favorite things to talk about because it is just a box. I recently read book, The Art of the Poetic Line by James Longenbach. It’s a great book, although I disagreed with the way he defined poetry. He claimed that poetry is the use of sound; the language in sound, based on lines, or something like that. I think poetry is language, and the sound of language in patterns. We have boxes in poetry even though poetry is this wide-open genre. But also, there are some tried and true things, like repetition. The more fixed forms have their constraints, like sonnets and villanelles. And then there are forms you can take from other things. For example, my poem that’s in the form of a CV. When you put yourself in some kind of box or when you put your voice in a box in poetry, that, to me, is a form. And there are forms that have more rules than others, but I like how form can warp the way we write, or even the way that we’re talking right now. So form is just a practice for me in making sure that the surprise stays in my poems. And I want the surprise to stay for me because if I’m not interested in what I’m writing, a reader’s not going to be either.

LO: Yes, I get that.

KB: So in that way, I think form shows up in this particular book by how I was thinking about the weirdest thing I could possibly do. I’m writing about the same thing all the time; how can I write about the same thing and make it interesting? I’ve never been into math, but I have been into patterns. I like the patterns of music, and the ones used by comedians. Like when you know that punchline is coming, but you don’t know how they’re gonna get there. I love that.

LO: Yes! Like the “callback” where they hit that perfect landing. So, I’d like to hear a little about your revision process, which isn’t a topic that comes up in poetry as much as it does in prose writing.

KB: Yes, and that definitely changes as the days change for me. But right now, I’m mostly avoiding it. I’m trying to generate more, and I really try not to edit while I’m generating. This is a first draft. I know it’s not what it’s gonna end up being, but I have to write it and sit it down and not look at it for a few weeks, then I’m gonna go back with the editorial brain. I’m also the kind of person who sometimes will write a poem and think, “this is the best poem I’ve ever written.” And then I look at it the next week and think it’s actually not good at all.

LO: But maybe the reverse of that also happens? Where you think, “ah, this is terrible!” But then you come back to it, and see there might be something there?

KB: Exactly. I never throw anything away. If it ends up getting cut from a poem or anything, when it’s whole lines and phrases that I’m cutting, I copy and paste, and put it in “scraps.” I have a document that’s over 100 pages called “scraps.”

LO: Great idea. I am a huge fan of the whole collection, of course, but especially the second-to-last poem, “Freedom House Manifesto.” I’m intrigued by how the opening line is ‘leisure for youth,’ and when you mention leisure earlier, I thought about the weight that word carries and especially for youth. I’m curious about how that all comes together in what you’re seeing.

KB: I think young people are literally an oppressed class. A lot of people, especially adults, project unfair stereotypes, and unfair expectations onto youth. A lot of people are still processing their childhood and still messing up their youth because of it. Right? And as a person who’s worked in an elementary school, I know that on the surface, with kids being disruptive, there could be so many other things going on. I think about how much the school system fails youth by not having things like housing support, food support, free food. Why is anybody paying for food at a place that they have to be at? That doesn’t make sense to me. I want to see housing support, food support, mental health support, and what you might call conflict transformation, where they can learn how to communicate with each other better. Sometimes people are rowdy because they haven’t eaten. It upsets me, especially the rhetoric around trans youth right now. The politicizing of youth. Not to say the youth aren’t political bodies; I think we very much should be listening more to youth when we’re thinking about things that impact their everyday lives.

I think what I want most for youth is for them to be able to be young. For them to be able not to have their childhood not taken away from them. So, when I say leisure for the youth, I mean they should not be protesting with picket signs. They should be able to go to class and have their basic needs met and not have to be the poster child for some ignorance around an issue. This is what I think is currently happening with trans youth. A lot of people are ignorant about that, so they are making things up. And I think that trans kids, as well as parents of trans kids, should be able to just live their lives. It upsets me when I see kids having to protest for their rights. It happens, unfortunately, especially in Texas.

LO: Definitely. Yes, thank you for that. I think that for a range of ages, certainly high school, maybe middle school, a lot of these poems are going to speak to young folks and inspire them to connect to their own writing and their own voice. That can be a part of them experiencing the joy of creation, creative thinking, and art. I think you getting this book out into the world is a way of inspiring youth to get into something fun for them; it could even be a way for them to experience leisure.

Let’s close with some ways readers can support you in your journey. Buying or pre-ordering the book is helpful for writers, but is there anything else that you would like to share about how folks can support you?

KB: The monetary way would be buying the book, and the non-monetary ways include requesting the book at your local libraries. It’s important to me that people are able to access the book for free. That includes public libraries, university libraries, and even the little free libraries that are in people’s neighborhoods. All those things, then also engaging with me on social media. I’m at ‘earthtoKB’ everywhere, but unfortunately, a lot of social media platforms are shadowbanning trans people, Black people, and anyone being critical of these apps. My visibility on social media directly relates to whether I get booked or not a lot of the time. Just liking or saving something could mean that 100 more people see the post. That stuff really does help. And commenting. All of those things on social media, along with coming to the events for my book tour this year.

KB BROOKINS is a Black, queer, and trans writer, cultural worker, and artist from Fort Worth, Texas. Their chapbook How To Identify Yourself with a Wound (Kallisto Gaia Press, 2022) won the Saguaro Poetry Prize and was named an American Library Association Stonewall Honor Book in Literature. KB’s debut full-length poetry collection Freedom House (Deep Vellum Publishing, 2023), and their memoir Pretty (Alfred A. Knopf, 2024) are both forthcoming.

LAUREN OERTEL is a community organizer covering Texas and New Mexico, based in Austin, Texas. Her work has been published in The Ravens Perch, Evening Street Review, The Bluebird Word, Noyo Review, and The Sun Magazine. She won first prize in the 2021 MONO.Fiction poetry competition and was a winner of the 2022 Writer’s Digest short story contest, as well as the 2022 Mendocino Coast Writers’ Conference poetry contest.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories, sports musings, or book reviews sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

NEW book release

Ghosts Caught on Film by Barrett Bowlin. Order the book of which Dan Chaon says “is a thrilling first collection that marks a beginning for a major talent.”

GET THE BOOK