AFTER HE MAPPED AND TATTOOED ME, Bill gave me a pamphlet titled Radiation Therapy and You. It was less than thirty pages long with large print, so I read the whole thing in the hospital cafeteria before I drove home. In every illustration, the doctors, the technicians, the nurses, and the patients were smiling. There were two patients featured in the pamphlet. For the breast cancer audience: a fit, middle-aged woman who wore workout clothes to her appointments. For the prostate cancer audience: an elderly gentleman wearing plaid pants who seemed to have just stepped off the golf course. Somehow, they forgot to include the fearful, thirty-something high school math teacher with Hodgkin’s.

In between each section of the pamphlet there was a random picture of a sunrise or a flower or a lighthouse. The pamphlet opened with: “Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high doses of radiation to kill cancer cells and stop them from spreading.” and stayed at that level of scientific detail. I did not learn a thing that I did not know already from the spiel Bill gave me while he was prepping me. The whole thing was written for a third, maybe a fourth-grade reading level. It made me question the hospital where I was getting my treatment. This cheesy pamphlet was the information packet they gave to someone getting treated for cancer?

The first sentence of the section on side-effects said, “Most of the side effects of radiation therapy will be mild and will not last long.”

It starts with a warm glow on my shoulders and the back of my neck as if I’ve stood out in the sun too long.

When my skin turns red, the technician, Bill, notices and gives me a jar of ointment that seems to be nothing more than Vaseline. Then, a couple of days later, I have welts, purple bumps that split open and ooze red goo. I ask for something stronger than Vaseline.

Bill says, “It’s only a second-degree burn. I’ve done as much going to the beach. If the skin starts to fall apart, then the doctor will give you something for it.”

Only second-degree? Skin falling apart? Every fifteen minutes Bill pops someone new up on the table and zaps them with radiation. Many of the people getting up on his table are going to die soon, and, given that, I guess burned flesh is not a big deal.

When the base of my neck starts to bleed, Bill tells me that the problem is that I am so damn skinny. “The dose we’re giving you is set for how thick your body is at the center of your chest. On your shoulder blades, you’re getting two, maybe three times the dose you should be getting.”

What happens when you get a triple dose of radiation in your shoulder blade? I take what Bill has said and put it in my growing mental file of things I wish I had not been told.

Bill gets me in with Dr. Fitzpatrick who prescribes a steroid cream which is supposed to help the skin rebuild itself. The burn is all over my neck, chest and back, and when I go to the pharmacy, I get a tube of cream the size of a Cracker Jack prize.

When I come back two days later asking for a new tube, the pharmacist says I’ll have to wait a week for my refill.

I tell her that I am burnt all over my chest and back and neck and that I can’t wait a week.

She tells me I am supposed to use it sparingly

“What fucking difference does it make if you give me an extra tube of cream? Do you really think that there is some way that I am abusing skin cream?”

I am a teacher, a husband and a father who lives in a small village. I cannot afford to say “fucking” in public places, but ever since I got the results from my biopsy, I haven’t quite been myself. Or, maybe this angry fellow is my real self.

I start to pull off my shirt to show her the burn. She asks me to please, please put my shirt back on. Once I’m standing there shirtless in the middle of the Rite Aid, the rage passes.

As I am putting my shirt back on, the pharmacist tells me that my doctor might be able to change the timing of the refills.

Doctor Fitzpatrick calls the pharmacist and, from then on, I am rolling in steroid cream, but, still, my skin turns into red jelly. Putting on a shirt is torture. I lie down at night, but I don’t sleep. I shiver constantly.

Then the doctor gives me a new prescription called Silvadine which feels and looks like cream cheese. When I let it sit on my skin it pulls black flakes out of the red jelly. I walk around my house shirtless, covered in Silvadine, dropping clumps of hardened cream with black speckles in my path.

My three-year-old son says, “Daddy, you’re shedding.” I worry about the father image I am projecting: a skinny, shirtless, shivering man who squats in front of the heating vent and drops pieces of skin all over the house.

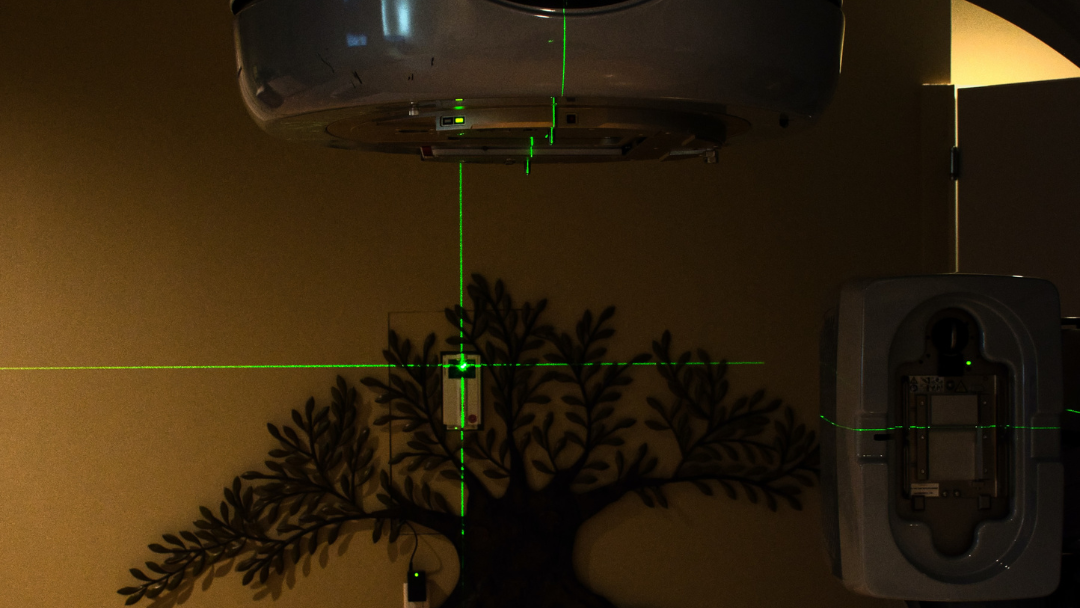

For the first couple of weeks of treatment, before the burn, I felt absolutely nothing. While I was lying on the table, I sometimes wondered if there was anything really coming out of the machine.

When I woke in the mornings, there was always a blank spot, a few seconds when I did not know where I was, what was happening. Then would realize: I have cancer. But after that, I would realize something else, something that made me feel better: I don’t have to go to work today. I had loads of sick time so I was taking a semester off for the treatment.

In the pamphlet they gave me, it said, “Other than the daily twenty-minute appointments, radiation therapy should not interfere with your life. Try to keep your life as full as possible and stick with enjoyable daily routines.”

During those first two weeks of treatment, I got into a sweet routine.

After treatment I went to the Y and swam laps and lifted weights.

Then I went to Eli’s Bagels and had bacon and egg on an everything while working on The New York Times Spelling Bee.

I usually picked my son up from day care early so we could go to the good playground in the village down the road where people paid higher taxes.

When we got home, I would lie on the floor with my son and play with trucks and blocks. Without work to worry about, I was much better at playing, at putting myself into a three-year-old state of mind.

Then I would make dinner. I’m no great cook, but I always had a plan for dinner, and there was less take out, more fresh food.

When my wife got home, I was better at listening to her talk about her day. We had sex more often. Maybe it was because she had pity on me, but whatever it was, I was glad for it.

I had this crazy idea that maybe I should give up my job and become a house husband. I did not miss teaching at all. My wife made a lot more money than I did and maybe if we cut back on our spending…

I was smart enough not to ever mention the idea of becoming a house husband.

The doctor lowers the amount of radiation they are shooting into me each day. He decides to zap me four days a week instead of five. But my skin will not heal. I look at the bright red welts on my chest and wonder if my skin will ever look normal again.

Finally, one day, I tell the technician that I need the doctor to look at the burn. When I take off my gown off in the examination room, the doctor says, “Looks like you were standing next to a grenade.” He decides to consult some colleagues and comes back with two other radiation oncologists. Now, you never want to be in an examining room with one oncologist, much less three, but part of me is glad because their attention says that I wasn’t just being a wimp.

They decide that a week off should give enough time for the skin to heal. With the lower dose and the time off, the number of radiation days needs to be refigured.

“So, we’re doing 150 a day, and we need 900 extra. That will be…”

Dr. Fitzpatrick goes to his phone calculator to figure it out. If he were one of my ninth graders, I would say, “Stop. Use your brain. You can solve this.” I do not say anything to my doctor.

After I get dressed, I walk by the three doctors in the hallway and hear them conferring about whether or not to keep someone on a respirator. It occurs to me that the reason that these guys came rushing to my examination room was because I was an easy case, a sun burn, a math problem.

With days off, with lower dosage, they get me through all of the treatment I am supposed to receive on my chest. I have two weeks off while they map me again and get ready to radiate my stomach. After a week and a half off, my chest, neck and shoulders have gone from blazing welts back to skin–flaking, callused and pockmarked skin–but skin that does not ache. I get back to my routine—The Y, Eli’s, the upscale playground.

Bill, the technician tells me that the next thing I have to worry about is that, when they radiate my stomach, I will likely have some nausea. He says the degree of nausea varies. “Some people lose appetite and can’t handle motion, but others are sick all the time. A month ago, I had a woman who was puking so much, every day, it was tough to keep her on the table for ten minutes.”

I say to him, “Bill, why the hell would you tell me that?”

“Sorry, man. She was a standout. That probably won’t be you.”

I decide to look at “Radiation Therapy and You” to see what it says about nausea. I do not do online searches about cancer anymore. The one time I made the mistake of searching on WebMD, I could not stop myself from reading facts that I was better off not knowing. I was stage two, but I could not help reading about stage four where the cancer can easily spread into the liver, the lungs, the bones. Some of the end-stage symptoms—fever, bone pain, abdominal pain– were things you could easily think were happening right now.

Before I read about nausea, I decide to look back at the burn section. It is less than one page. It compares radiation burn to a minor sunburn and does not describe anything like the kind of damage I saw on my skin.

I do not end up reading the section on nausea. Probably best not to think too far ahead. Instead, I keep rereading the final line of the burn section and looking at the photo next to it. The picture shows the sun rising over the ocean and shining onto a lighthouse. The pamphlet says, “There are not likely to be any scars from radiation burn because human skin has an amazing capacity for healing.”

JOHN SANDMAN recently retired from a twenty-eight-year career as an English Professor at The State University of New York at Delhi. He has published stories in The MacGuffin, ellipsis and West Branch.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories, sports musings, or book reviews sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

NEW book release

Ghosts Caught on Film by Barrett Bowlin. Order the book of which Dan Chaon says “is a thrilling first collection that marks a beginning for a major talent.”

GET THE BOOK